Egypt, under the leadership of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, is becoming quite adept at playing pyramid games across the Middle East and North Africa. Allegorically speaking, Cairo inducing two or more competing governments to invest in the same real estate underpins el-Sisi’s core strategy to play allies off one another.

Geostrategically, Egypt’s pyramid game has long engulfed the opposing interests of Russia and the United States. For example, despite Russian President Vladimir Putin’s illegal war of aggression against Ukraine, el-Sisi is continuing his efforts to balance and deepen economic and military ties with Washington and Moscow.

In July 2022, five months after the start of the war in Ukraine, Russia began construction of Egypt’s first nuclear power plant. The $30 billion facility, located 190 miles west of Alexandria, is being constructed by the Russian State Atomic Energy Corporation and financed by Russia at 3% over 22 years.

The U.S. response later that year was to go green. During the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Sharm El Sheikh, located at the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, the U.S., in partnership with Germany, allocated $250 million intended to “unlock $10 billion in commercial investment to support Egypt’s clean energy economy.”

Beyond encouraging wind and solar energy development, Washington has consistently invested heavily in Egypt’s military capabilities since 1978, the year Egypt and Israel signed the Camp David Accords. According to the U.S. Embassy in Cairo, that now tops $50 billion to help the country “protect and defend its land and maritime borders and to confront an evolving terrorist threat, including in the Sinai Peninsula.”

Yet, despite U.S. aid, Cairo continues to deepen its close ties with the Russian military, which began during the Soviet era. Gamal Abdel Nasser, then the president of Egypt, turned to the Kremlin to finance and complete the construction of the Aswan Dam — a partnership that quickly evolved into military cooperation.

Notably, this June, the Russian and Egyptian navies conducted joint naval exercises in the Mediterranean Sea near Alexandria. Last year, The Biden administration was forced to threaten Cairo over its plans to sell rockets to Putin in support of his “special military operation” in Ukraine. Instead, Egypt agreed to artillery shells to Kyiv.

Contrast that with the annual U.S. and Egyptian Armed Forces BRIGHT STAR exercise that is conducted each year along with over 30 participating nations at Mohamed Naguib Military Base in Egypt. The BRIGHT STAR 2023 exercise was built upon the decadeslong strategic partnership between the U.S. and Egypt, and it focused “on regional security and cooperation while promoting interoperability in conventional and irregular warfare scenarios.”

Cairo’s pyramid game involving the superpowers, however, is not going away. In January, Egypt, alongside Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, became a full member of BRICS — the economic bloc dominated by Russia, China, India, and Brazil.

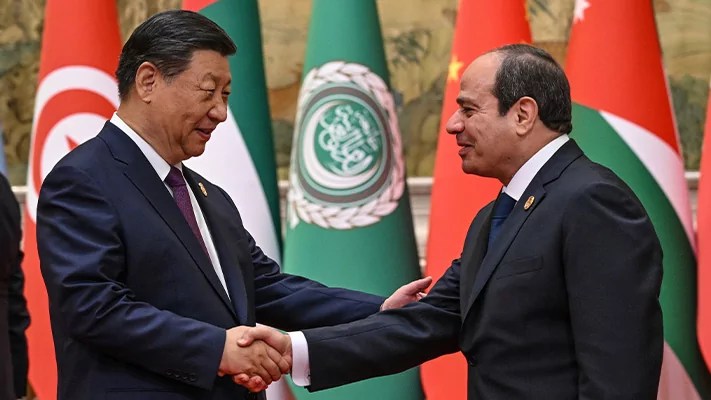

In May, el-Sisi traveled to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping. While in Beijing, the two leaders marked the 10th anniversary of the Egypt-China strategic partnership. In the last two years alone, Beijing has invested nearly $30 billion in Egypt as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

That includes $2 billion in the Suez Economic Zone to construct steel and iron plants and a May announcement that China’s Hutchison Ports is building a 1.6-million-square-meter shipping container terminal at the Ain Sokhna port on the Red Sea. When completed, it will be Egypt’s largest.

Regionally, Egypt’s pyramid game is at its most insidious in Gaza, and it is an even deeper one involving tunnels between Egypt and the strip. It is also a multilayered complex web that has evolved significantly over the last decade.

Initially, when el-Sisi assumed power in 2014, his regime took a hard line against Hamas in the Gaza Strip and aggressively worked in partnership with Israel to blockade Gaza and undermine Iran’s terrorist proxy.

This included, according to Maged Mandour at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Egypt destroying “Hamas’ supply chains, particularly the vital tunnels transporting foodstuffs, fuel, construction materials, and medical supplies into the besieged strip.” Cairo even tried flooding the tunnels connecting Gaza with Egypt.

Yet, beginning in 2017, faced with a growing Islamic State insurgency kinetic threat in the Sinai, el-Sisi strategically “pivoted to a policy of cooperating with Hamas.” The full impact of that change was not fully understood until Oct. 7, 2023 — nor the scope of it until after the Israeli military discovered what was being transported in those tunnels after it seized the Rafah border crossing in early May.

Until then, Jerusalem was content to use Egypt’s growing cooperation with Hamas to ensure it could mediate outbreaks of rocket attacks being launched from Gaza and aimed at southern and central Israel. Mediation, in that narrow vein, helped mitigate against the need for an all-out war against Hamas.

However, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu misread the extent to which el-Sisi was playing him. More than just food, medicine, and construction supplies were passing through those tunnels. It is highly likely that so, too, were some of the equipment, arms, and munitions that were used by Hamas to attack Israel on Oct. 7.

According to an Associated Press report in January that analyzed 150 videos, Hamas uses “a diverse patchwork arsenal of weapons from around the world,” including sniper rifles made in Iran, Chinese and Russian AK-47 assault rifles, and rocket-propelled grenades manufactured in North Korea and Bulgaria. Most were likely smuggled through the Rafah crossing — and the tunnels below reaching into the Sinai.

Israel’s decision to seize the strategic 9-mile border crossing, commonly referred to in the region as the Philadelphi Corridor, was largely due to the continued flow of arms and munitions into Israel after the start of the Israeli military’s operations in Gaza. Egypt, wittingly or not, was enabling the arming of Hamas.

Egypt’s pyramids were built to last — the Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed roughly 4,600 years ago. Pyramid games are not, and el-Sisi’s are beginning to fall apart in the light of day under their weight.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

For now, the Suez Canal affords Egypt the leverage and economic cover Cairo needs to continue to play all the competing actors off one another. When you play with fire though, you eventually get burned.

Washington, Moscow, Beijing, and Jerusalem are at bay for now. However, Suez Canal or not, like all investors, they will eventually demand a return on their investments or a return on their capital — and when they do, Egypt and el-Sisi are likely to be caught shorthanded.

Mark Toth writes on national security and foreign policy. Col. (Ret.) Jonathan Sweet served 30 years as a military intelligence officer and led the U.S. European Command Intelligence Engagement Division from 2012 to 2014.