Draft:Original research/Evolution

Biological evolution is change among generations. It is a fact of biology that evolution occurs. Parents and children of non-clonal (sexually reproducing) species are not exactly alike. Further, grandparents and grandchildren in those species are more dissimilar. That in and of itself is evolution.

There are several theories and hypotheses about how evolution occurs, what drives or allows evolution, and how the evolutionary history of life on Earth has unfolded.

The current dominant scientific theory about the main cause of evolution is the Theory of Evolution by Means of Natural Selection, formulated and set forth by Charles Darwin in 1859 in his book "On the Origin of Species." Though that theory has been added too, clarified, and modified in details, the theory remains the foundation of all modern biology.

Theodosius Dobzhansky, a pioneering geneticist, is famously quoted that "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution".

Natural Selection

[edit | edit source]The Theory of Evolution by Means of Natural Selection, formulated and set forth by Charles Darwin is the foundation of all modern biology.

The theory holds that:

- Individual organisms within a species (or population) are not identical.

- The differences can be passed on by some mechanism (Darwin didn't know about genetics, we now know that's the mechanism).

- The differences among individuals in a species make some more suited for their environment.

- Not all organisms in a generation will reproduce.

- The individuals that have "more suited" differences are those that produce more offspring in the next generation.

Differences that make an organism "more suited" to their environment are called adaptations. For example, having limbs is an adaptation to moving efficiently along surfaces. It's not the only possible adaptation for such locomotion (snakes don't have limbs, for instance). A trait that does not give some advantage to an organism within an environment is not considered an adaptation, however it may have served as a adaptation at some point in the evolutionary history of an organism. The evolutionary process can be described with three steps: mutation – selection -reproduction.

Evolution as a scientific cognition and innovation process.

[edit | edit source]Darwin's and Wallace's theory of evolution describes a scientific cognition and innovation process. [1]

- The mutation corresponds to setting up a model.

- The selection corresponds to testing a model.

- The reproduction corresponds to publishing a model.

The evolutionary process does not strive for any specific goals, but produces innovations and evolutionarily stored knowledge.

Radiation

[edit | edit source]

An evolutionary radiation is an increase in taxonomic diversity or morphological disparity, due to adaptive change or the opening of ecospace.[2] Radiations may affect one clade or many, and be rapid or gradual; where they are rapid, and driven by a single lineage's adaptation to their environment, they are termed adaptive radiations.[3]

Perhaps the most familiar example of an evolutionary radiation is that of [Eutheria] placental mammals immediately after the extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous, about 65 million years ago. At that time, the placental mammals were mostly small, insect-eating animals similar in size and shape to modern shrews. By the Eocene (58–37 million years ago), they had evolved into such diverse forms as bats, whales, and horses.[4]

The Hawaiian lobelioids are a group of flowering plants in the [Campanula] bellflower family, Campanulaceae, all of which are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. This is the largest plant radiation in the Hawaiian Islands, and indeed the largest on any island archipelago, with over 125 species.

In 1960, with respect to the theory of evolutionary progressivism, Huxley wrote "Improved organization gives biological advantage. Accordingly, the new type becomes a successful or dominant group. It spreads and multiplies and differentiates into a multiplicity of branches. This new biological success is usually achieved at the biological expense of the older dominant group from which it sprang or whose place it had usurped."[5]

Planetary sciences

[edit | edit source]

Def. the "action of making or becoming"[6] no "longer in existence; having died out"[7] is called extinction.

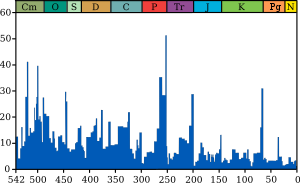

Def. the apparent percentage (not the absolute number) of marine animal genera represented by those that are readily fossilized becoming extinct during any given time interval is called the genus extinction intensity.

"Many of the extinction events appear to be somewhat extended in time. In at least some cases this is the result of a paleontological artifact known as the Signor-Lipps effect (Signor & Lipps 1982). Briefly, this is the observation that inadequate sampling can cause a taxon to seem to disappear before its actual time of extinction. This has the effect of making an extinction event appear extended even if it occurred quite rapidly. Hence, when estimating the true magnitude of an extinction event it would be common to combine together the events occurring over several preceding bins as long as they also show excess extinctions. This explains why many estimates of the magnitude of an extinction event may be larger than the 20-30% shown as the largest single bin for most of the extinctions shown here."[8]

On page 212 of a 1944 book by Simpson is "[i]n the history of life it is a striking fact that major changes in the taxonomic groups occupying various ecological positions do not, as a rule, result from direct competition of the groups concerned in each case and the survival of the fittest, as most students would assume a priori. On the contrary, the usual sequence is for one dominant group to die out, leaving the zone empty, before the other group becomes abundant."[9] "Simpson noted that major extinctions provide opportunities (space, ecological niches, etc.) for later diversification by the survivors."[10]

Colors

[edit | edit source]Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including biodiversity species, individual organisms and molecular evolution molecules such as DNA and proteins.[11]

Theoretical evolution

[edit | edit source]

Def. "gradual directional change especially one leading to a more advanced or complex form"[12] is called evolution.

Def. "[t]he change in the genetic composition of a population over successive generations"[12] is called evolution.

Def. any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations is called evolution.

Modern evolutionary synthesis: "Other previously dominant groups of organisms that also became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous are many marine taxa, such as most nautiloids and the ammonities, both of whom had been previously highly successful organisms."[13] Page 320 of the 2001 book: "Ernst Mayr is the biologist largely responsible for shaping the modern synthesis of genetics and evolutionary theory."[13]

"The central problem with the synthesis is its failure to show (or to provide distinct signs) that natural selection of random mutations could account for observed levels of adaptation."[14]

Entities

[edit | edit source]The earliest use of "dominant groups" in the theory of natural selection is by Charles Darwin on page 343 of his book, On the origin of the species by means of natural selection: or, The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life: “The dominant species of the larger dominant groups tend to leave many modified descendants, and thus new sub-groups and groups are formed.”[15]

Later in 1860, “Under the many conditions of life which this world affords, any group which is numerous in individuals and species and is widely distributed, may properly be called dominant" [a dominant group]. [Letter 110. To W.H. Harvey, August, 1860][16]

Evolution by means of natural selection is the process by which genetic mutations that enhance reproduction become and remain, more common in successive generations of a population. It has often been called a "self-evident" mechanism because it necessarily follows from three simple facts:

- Heritable variation exists within populations of organisms.

- Organisms produce more offspring than can survive.

- These offspring vary in their ability to survive and reproduce.

These conditions produce competition between organisms for survival and reproduction. Consequently, organisms with traits that give them an advantage over their competitors pass these advantageous traits on, while traits that do not confer an advantage are not passed on to the next generation.[17]

The central concept of natural selection is the [fitness in biology] evolutionary fitness of an organism.[18] Fitness is measured by an organism's ability to survive and reproduce, which determines the size of its genetic contribution to the next generation.[18] However, fitness is not the same as the total number of offspring: instead fitness is indicated by the proportion of subsequent generations that carry an organism's genes.[19] For example, if an organism could survive well and reproduce rapidly, but its offspring were all too small and weak to survive, this organism would make little genetic contribution to future generations and would thus have low fitness.[18]

Natural selection produces dominant groups of organisms. But, do dominant groups of organisms then produce new species?

Over time, this process can result in populations that specialize for particular ecological niches and may eventually result in the emergence of new species, without a citation. The original inserted text is "Over time, this process can result in adaptations that specialize organisms for particular ecological niches and may eventually result in the emergence of new species, an event known as speciation."[20]

Sources

[edit | edit source]Def. a theory of inheritance based on a modification and extension of Lamarckism, essentially maintaining the principle that genetic changes can be influenced and directed by environmental factors is called Neo-Lamarckism.

"Perhaps more revealing would be to ask this group of molecular geneticists to describe Lamarckism versus Mendelism. ... These examples characterize a lack of integrative capability that exists in the contemporary and dominant group of gene specialists."[21]

Objects

[edit | edit source]Def. the "view that objects have properties that are essential to them"[22] is called essentialism.

With the beginnings of biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, Western biological thinking was influenced by essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics that fit well with natural theology.

Essentialism is the view that, for any specific kind of entity, there is a set of characteristics or properties all of which any entity of that kind must possess. All things can therefore be precisely defined or described. In this view, it follows that terms or words should have a single definition and meaning.[23]

The essential properties of a tiger are those without which it is no longer a tiger. Other properties, such as stripes or number of legs, are considered inessential or 'accidental'.[24]

Biologist Ernst Mayr epitomizes the effect of such an essentialist character of [Platonic realism] Platonic forms in biology: "Flesh-and-blood rabbits may vary, but their variations are always to be seen as flawed deviation from the ideal essence of rabbit". For Mayr, the healthful antithesis of essentialism in biology is "[population biology] population thinking".[25]

Recent work by historians of systematics Mary P. Winsor, Ron Amundson and Staffan Müller-Wille argues that the usual suspects (such as Linnaeus and the Ideal Morphologists) were very far from being essentialists, and it appears that the so-called "essentialism story" (or "myth") in biology is a result of conflating the views expressed by philosophers from Aristotle onwards through to John Stuart Mill and William Whewell in the immediately pre-Darwinian period, using biological examples, with the use of terms in biology like species.[26][27][28]

"An essentialist view of a given species is committed to there being some property which all and only the members of that species possess."[29] "The essentialist requires that a species be defined in terms of the characteristics of the organisms which belong to it."[29] "Diversity [may] be accounted for as the joint product of natural regularities and interfering forces."[29]

Strong forces

[edit | edit source]

Def. the "return of a genetic characteristic after a period of suppression"[30] is called a reversion.

In botany, a sport or bud sport is a part of a plant (normally a woody plant, but sometimes in herbs as well) that shows morphological differences from the rest of the plant. Sports may differ by foliage shape or color, flowers, or branch structure. Sports with desirable characteristics are often propagated vegetatively to form new cultivars that retain the characteristics of the new morphology. Such selections are often prone to "reversion", meaning that part or all of the plant reverts to its original form.

A back mutation or reversion is a point mutation that restores the original sequence and hence the original phenotype.[31]

Gradualism

[edit | edit source]Def. "belief that evolution proceeds at a steady pace, without the sudden development of new species or biological features from one generation to the next"[32] is called gradualism.

Saltationism

[edit | edit source]Def. "belief that evolution operates by the sudden development of new species or biological features from one generation to the next"[33] is called saltationism.

Def. a "sudden change from one generation to the next"[34] is called saltation.

Polyploidy (most common in plants but not unknown in animals) is considered a type of saltation.[35] But, Dufresne never used the term "saltation" in his article.[35]

"Work of systematists [2] and geneticists [3 and 4], on the stages of speciation, confirmed Darwin's view that speciation rarely involves discontinuous 'saltations' (polyploidy being the principal exception)."[14]

Punctuationism

[edit | edit source]Def. "belief that evolution does not proceed at a steady pace, but instead is characterized by periods of stasis, punctuated by brief (within several hundred-thousand years) periods of rapid change"[36] is called punctuationism.

Teleology

[edit | edit source]Def. the "study of the purpose or design of natural occurrences"[37] is called teleology.

A teleology is any philosophical account which holds that final causes exist in nature, meaning that design and purpose analogous to that found in human actions are inherent also in the rest of nature. In modern science, an explanation that relies on teleology is avoided, because whether they are true or false is argued to be beyond the ability of human perception and understanding to judge.[38] But using teleology as an explanation style, in particular within evolutionary biology, is still controversial.[39] Apparent teleology is a recurring issue in evolutionary biology,[40] much to the consternation of some writers.[39] Statements which imply that nature has goals, for example where a species is said to do something "in order to" achieve survival, appear teleological, and therefore invalid.

Transmutation of species

[edit | edit source]

Def. the process of changing, transforming or converting one species into another, or from one species into another, is called transmutation of species.

In the early 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

Lamarck became convinced of the transmutation of species during the period 1797-1800. He used Trigonia as a prime example of a once-dominant group [in the Mesozoic] which had been drastically restricted in diversity, abundance, and geographic range"[41] down to one genus Neotrigonia and five living species. All are found off the coast of Australia.

Vitalism

[edit | edit source]Def. "the doctrine that life involves some immaterial "vital force", and cannot be explained scientifically"[42] is called vitalism.

Vitalism, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary,[43] is

- a doctrine that the functions of a living organism are due to a vital principle distinct from biochemical reactions

- a doctrine that the processes of life are not explicable by the laws of physics and chemistry alone and that life is in some part self-determining.

Other vitalists included Johannes Reinke and Oscar Hertwig] Reinke used the word neovitalism to describe his work, he claimed that it would be eventually verified through experimentation and wanted an improvement over the other vitalistic theories. The work of Reinke was an influence for Carl Jung.[44]

Hypertrophy

[edit | edit source]"The inheritance of acquired traits, also known as his 'Second Law' in Philosophie Zoologique, is the idea that the traits of an organism that undergo hypertrophy will be inherited by the next generation. This hypertrophy suggests an adaptation to the environment that can be passed on to the next generation through the genetic code of the organism."[45]

"The Lamarckian view of evolution is seen as a tendency for a species to reach perfection where it is actually simply adapting to their environment in a single generation."[45]

Transmissions

[edit | edit source]"The development of organs and their power of action are continually determined by the use of these organs." This is known as his [Lamarck's] third law. In the fourth he insisted on the hereditary nature of the effects of such use. "All that has been acquired, begun or changed," he said, "in the course of their life is preserved in reproduction and transmitted to the new individuals which spring from those which have experienced the changes."[46]

Extinctions

[edit | edit source]"Lamarck did not believe that a species could become extinct. Instead, he saw the idea of extinction as every member of a species evolving into another species. He believed that change was brought about through use and disuse and inheritance of acquired characteristics. This was the first time that a mechanism was proposed in order to explain how a change in a species occurred."[45]

Biochemistry

[edit | edit source]Def. a "series of similar mutations in successive generations, producing evolutionary change"[47] is called orthogenesis.

"Orthogenesis ... is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to evolve in a unilinear fashion due to some internal or external "driving force". The hypothesis is based on essentialism and cosmic teleology and proposes an intrinsic drive which slowly transforms species. ... Classic proponents of orthogenesis have rejected the theory of natural selection as the organising mechanism in evolution, and theories of speciation for a rectilinear model of guided evolution acting on discrete species with "essences". The term orthogenesis was popularized by Theodor Eimer, though many of the ideas are much older (Bateson 1909).[48]

"Many other principles, such as those concerned with reversion and orthogenesis, are gradually being formulated and it is only a matter of time and more extended observation before the science of phylogeny will be placed on a much more uniform and exact footing. ... The ancestors of our modern hexapods achieved their first success through some advance in specialization over this more primitive type, but the improvements which gave them ascendancy and which enabled them to found a distinct and dominant group were certain unknown changes, doubtless in plastic and functionally important characters which were of great value for survival at the time, but which, having isolated the family and put it on its feet, so to speak, continued to change and may be possessed by few or no living descendants."[49] Bold added.

Hypotheses

[edit | edit source]- Changing conditions, not necessarily for the better, have resulted in persistent life forms evolving to more durable life forms able to survive the changes.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Ammonoids (62 kB) (22 September 2019)

- Animal physiology (8 kB) (12 September 2019)

- Anthropology (Aftonian, 540 ka) (30 kB) (29 March 2019)

- Archaeology (-12th Century) (70 kB) (10 September 2019)

- Biology (22 kB) (15 January 2020)

- Botany (82 kB) (24 February 2019)

- Brain (2 kB) (1 October 2019)

- Cenozoic (Danian) (231 kB)

- Cytogenetics (12 kB) (28 March 2019)

- Cytokinesis (12 kB) (29 October 2019)

- Dates (Hadean) (173 kB)

- Dominant group evolution

- Dominant group/Metagenome (65 kB) (28 March 2019)

- Epigenetics (27 kB) (5 November 2019)

- Epigenomes (27 kB) (5 November 2019)

- Eukaryotes (9 kB) (5 November 2019)

- Evolution (39 kB) (8 August 2019)

- Genealogy (6 kB) (12 September 2019)

- Gene project (4 kB) (1 April 2019)

- Genomes (25 kB) (28 May 2019)

- Genomics (13 kB) (28 May 2019)

- Heredity (11 kB) (18 December 2019)

- History (Hadean) (163 kB) (13 January 2020)

- Hominins (Miocene) (37 kB) (20 September 2019)

- Human DNA (Paleogene) (168 kB) (19 August 2019)

- Human physiology (2 kB) (14 March 2018)

- Human RNA (31 kB) (5 November 2019)

- Human teeth (None) (30 kB) (15 December 2019)

- Lamarckism (20 kB) (9 January 2020)

- Libyan history (Oligocene) (29 kB) (13 August 2019)

- Mammalogy (Oligocene) (26 kB) (10 September 2019)

- Melanocytes (49 kB) (17 September 2019)

- Paleanthropology (Paleogene) (195 kB) (30 August 2019)

- Paleontology (Hadean) (115 kB) (11 January 2020)

- Teeth (Prehistory) (24 kB) (9 October 2019)

- Zoology (177 kB) (26 November 2019)

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Fröhlich, Klaus (2023). "Scientific-Philosophical Base of Darwin's and Wallace's Theory of Evolution". Science & Philosophy - Journal of Epistemology, Science and Philosophy 11 (1): 158-178. doi:10.23756/sp.v11i1.1228.

- ↑ G. D. Wesley-Hunt (2005). "The morphological diversification of carnivores in North America". Paleobiology 31: 35–55. doi:10.1666.2F0094-8373.282005.29031.3C0035:TMDOCI.3E2.0.CO.3B2.

- ↑ Schluter, D. (2000). The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ This topic is covered in a very accessible manner in Chapter 11 Richard Fortey (1997). Life: An Unauthorised Biography.

- ↑ Stephen Jay Gould (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 1433. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=nhIl7e61WOUC&printsec=frontcover&hl=en. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ extinction. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 28, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/extinction. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ extinct. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 16, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/extinct. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ "File:Extinction Intensity.svg". Wikimedia Commons (San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc). July 6, 2012. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Extinction_Intensity.svg. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ George Gaylord Simpson (1944). Tempo and Mode in Evolution. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 237.

- ↑ David M. Raup (July 1994). "The role of extinction in evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 (15): 6758-63. http://www.pnas.org/content/91/15/6758.full.pdf. Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- ↑ B. K. Hall, B. Hallgrímsson, ed (2008). Strickberger's Evolution (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett. p. 762. ISBN 0763700665. http://www.jblearning.com/catalog/9780763700669/.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 evolution. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. December 23, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/evolution. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ernst Mayr (2001). What Evolution Is. New York: Basic Books. pp. 336. ISBN 0-465-04425-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=i8jx-ZyRRkkC&printsec=frontcover&hl=en#v=onepage&f=false. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Egbert Giles Leigh Jr. (December 1999). "The modern synthesis, Ronald Fisher and creationism". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 14 (12): 495-8. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01725-5. http://bill.srnr.arizona.edu/classes/449/Opinion/Leigh%20-%201999.pdf. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- ↑ Charles Robert Darwin (1859). On the origin of the species by means of natural selection: or, The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray. pp. 516. http://books.google.com/books?id=_cvGifvlQiIC&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ↑ Charles Robert Darwin (October 1902). Francis Darwin and A. C. Seward. ed. More Letters of Charles Darwin A Record of his Work in a Series of Hitherto Unpublished Letters Volume I.. Cambridge. http://www.writersmugs.com/books/books.php?book=17&name=Charles_Darwin&title=MORE_LETTERS_OF_CHARLES_DARWIN. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Hurst LD (2009). "Fundamental concepts in genetics: genetics and the understanding of selection". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (2): 83–93. doi:10.1038/nrg2506. PMID 19119264.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Orr HA (2009). "Fitness and its role in evolutionary genetics". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (8): 531–9. doi:10.1038/nrg2603. PMID 19546856. PMC 2753274. //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2753274/.

- ↑ Haldane J (1959). "The theory of natural selection today". Nature 183 (4663): 710–3. doi:10.1038/183710a0. PMID 13644170.

- ↑ Opabinia regalis (March 21, 2007). Natural selection. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Natural_selection&diff=116698492&oldid=116301458. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- ↑ Leslie C. Costello (April 2009). "Perspective: The Effect of Contemporary Education and Training of Biomedical Scientists on Present and Future Medical Research". Academic Medicine 84 (4): 459-63. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a7c6b. http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Abstract/2009/04000/Perspective__The_Effect_of_Contemporary_Education.18.aspx. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ essentialism. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 31, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/essentialism. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ Günter Radden, H. Cuyckens (2003). Motivation in language: studies in honor of Günter Radden. John Benjamins. p. 275. ISBN 9781588114266. http://books.google.com/books?id=qzhJ3KpLpQUC&pg=PA275&cd=3#v=onepage&f=false.

- ↑ Lawrence A. Hirschfeld, "Natural Assumptions: Race, Essence, and Taxonomies of Human Kinds", Social Research 65 (Summer 1998). Infotrac (December 24, 2003).

- ↑ Both Mayr quotes in Dawson 2009:24, 25.

- ↑ Amundson, R. (2005) The changing rule of the embryo in evolutionary biology: structure and synthesis, New York, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521806992

- ↑ Müller-Wille, Staffan. 2007. Collection and collation: theory and practice of Linnaean botany. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38 (3):541–562.

- ↑ Winsor, M. P. (2003) Non-essentialist methods in pre-Darwinian taxonomy. Biology & Philosophy, 18, 387–400.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Elliot Sober (September 1980). "Evolution, population thinking, and essentialism". Philosophy of Science 47 (3): 350-83. http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/jbeatty/Sober1980.pdf. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- ↑ reversion. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 30, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/reversion. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ Ellis NA, Ciocci S, German J (2001). "Back mutation can produce phenotype reversion in Bloom syndrome somatic cells". Hum Genet 108 (2): 167–73. doi:10.1007/s004390000447. PMID 11281456. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00439/bibs/1108002/11080167.htm.

- ↑ gradualism. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 4, 2010. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/gradualism. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ saltationism. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. December 17, 2006. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/saltationism. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ saltation. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 3, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/saltation. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 France Dufresne, Paul D. N. Herbert (November 1994). "Hybridization and origins of polyploidy". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 258 (1352): 141-6. http://www.jstor.org/pss/49988. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- ↑ punctuationism. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. March 26, 2010. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/punctuationism. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ teleology. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 5, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/teleology. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ "The received intellectual tradition has it that, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, revolutionary philosophers began to curtail and reject the teleology of the medieval and scholastic Aristotelians, abandoning final causes in favor of a purely mechanistic model of the Universe." Monte Ransom Johnson. Aristotle on Teleology. Oxford University Press. pages 23-24.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Hanke, David (2004). John Cornwell. ed. Teleology: The explanation that bedevils biology, In: Explanations: Styles of explanation in science. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 143–155. ISBN 0-19-860778-4. http://books.google.com/?id=ZWpq14vS7WQC&pg=PA143. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Ruse, M., & Travis, J. (Eds.) (2009). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- ↑ Stephen Jay Gould (March 1968). "Trigonia and the origin of species". Journal of the History of Biology 1 (1): 41-56. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00149775?LI=true. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ vitalism. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 30, 2012. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/vitalism. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster definition

- ↑ Jung's Concept of Die Dominanten (The Dominants) Online

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Evolutionary Biology/Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 15 October 2012. http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Evolutionary_Biology/Jean-Baptiste_Lamarck. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ↑ Lamarck (April 14, 2012). On Modification and Variation. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/On_Modification_and_Variation. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ↑ orthogenesis. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 27, 2011. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/orthogenesis. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ The evolutionary future of man: A biological view of progress

- ↑ Edmund W. Sinnott (December 1913). "The Fixation of Character in Organisms". The American Naturalist 47 (564): 705-29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/2455528.pdf. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

Further reading

[edit | edit source]- Stephen Jay Gould (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 1433. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=nhIl7e61WOUC&printsec=frontcover&hl=en. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

External links

[edit | edit source]- African Journals Online

- Bing Advanced search

- GenomeNet KEGG database

- Google Books

- Google scholar Advanced Scholar Search

- Home - Gene - NCBI

- JSTOR

- Lycos search

- NCBI All Databases Search

- NCBI Site Search

- Office of Scientific & Technical Information

- PsycNET

- PubChem Public Chemical Database

- Questia - The Online Library of Books and Journals

- SAGE journals online

- Scirus for scientific information only advanced search

- SpringerLink

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Wiley Online Library Advanced Search

- Yahoo Advanced Web Search

{{Anthropology resources}}{{Archaeology resources}}

{{Gene project}}{{Geology resources}}{{Phosphate biochemistry}}{{Reasoning resources}}{{Sciences resources}}

|

Learn more about Evolution |

|

Learn more about Extinct animals |

|

Learn more about Extinction |

- Agriculture/Resources

- Animals/Resources

- Anthropology/Resources

- Archaeology/Resources

- Biochemistry/Resources

- Biology/Resources

- Botany/Resources

- DNA/Resources

- Dominant group/Resources

- Earth sciences/Resources

- Ecology/Resources

- Eukaryotes/Resources

- Evolution/Resources

- Genes/Resources

- Genetics/Resources

- Geography/Resources

- Geology resources

- Historical geology/Resources

- History/Resources

- Humans/Resources

- Humanities/Resources

- Immunology/Resources

- Paleontology/Resources

- Planetary sciences/Resources

- Plant sciences/Resources

- Probability/Resources

- Psychology/Resources

- Resources last modified in January 2020

- Scientific terminology/Resources

- Sciences/Resources

- Social psychology/Resources

- Sociology/Resources

- Statistics/Resources

- Sustainability/Resources

- Theory/Resources

- Zoology/Resources