User:B9 hummingbird hovering/Blog/Personal Weblog/Nonduality

Meta-information

[edit | edit source]If you happen upon this weblog sandbox and are interested in corresponding with or befriending me, please refer Internet Cyber Register for appropriate channels and forums, particularly my preferred email address in small print. It may take me in excess of 20 years to finish this work but by the grace of that which is divine and divinely pragmatic, nothing in this world will obstruct me come what may: friendlessness, absence of family, lovelessness, homelessness, loss of health and wellbeing, poverty. The code will be published in an appropriate open, free, accessible and reputable forum for peer review in time. I have not sought to plan an overt structure as this engenders insidious bias but a natural structure has and will continue to grow organically as the project projects. I am hopeful that a clear, intelligible and intuitive structure(s) and/or themes will gracefully present themselves.

- May these loci as gossamer threads of germane discourse ensue as seed-beads caressed with heartful love as benevolent and sensate action on a threaded rosary of sublime and auspicious living!

Until that hallowed point, this endgame will continue as an embedded discourse, ie. a mess and a muddle but no less informative, instructive and indeed edifying for that. Blessings B9hummingbirdhovering (aka Beauford Anton Stenberg).

Maṇībhadantānkuśa: Bejewelled Ankush of Ivory; or alternatively: Nonduality, Transpersonal Psychology, Subjectivity and the Human Condition: an embedded narrative

[edit | edit source]Maṇībhadantānkuśa: Bejewelled Ankush of Ivory; or alternatively: Nonduality, Transpersonal Psychology, Subjectivity and the Human Condition: an embedded narrative is the working title of this engaged, reflective investigation. I define terms as I value precision and I also understand that ambiguity has its usage and place. My endeavour at precision is not to close the openness of what I write, but to assist the comprehension and thereby the reception of this overview. This work is twofold, it is a cursory exploration of "nonduality" in the wisdom traditions of the World's peoples and I have chosen selectively and with purpose. Incidentally, it will identify a global development that is not real in any true sense as is just the construction of the works of a number of academic specialists such as historians, anthropologists, linguists and archeologists. That said, the development is real and there is no contradiction. This work is also the fruit of my reflection of human spiritual thought and praxis and my experience of that value.

Ankusha

[edit | edit source]A note on the Sanskrit title, Bejewelled Ankush of Ivory: Maṇībhadantānkuśa. Full Sanskrit title: Maṇībhadantānkuśa: Śrīmaharatnaikacittatvasaṃtānasvasaṃvedanaṃ; English: The Bejewelled Ankusha of Ivory: The Great Precious Glory; The Continuum of the Apperceptive Reflexivity of the Inclusive Nature of the Heartmind. Sanskrit written works, like Tibetan works following them, often have many names: one often contains a metaphor or analogy and another that conveys its meaning. Maṇībhadantānkuśa: Śrīmaharatnaikacittatvasaṃtānasvasaṃvedanaṃ. In the artifice of giving this English work a Sanskrit title I am following an ancient lineage and positing this work within that lineage. The Bejewelled Ankusha of Ivory: The Great Precious Glory; The Continuum of the Appercetive Reflexivity of the Inclusive Nature of the Heartmind. Citta essentially means both "heart" and "mind" or the most essential, heartful, cordial and pure aspect of our consciousness and being. Heartmind is a gloss of Bodhicitta principally from English renderings of Zen works, but the rendering has been adopted by other Buddhadharma traditions, particularly some teachers of Dzogchen and Mahamudra. I like its simplicity and its accessibility and subsequently, it is my favourite rendering for the "pure and perfect mind" (citta) of "awakening" (bodhi). Citta in the title is affixed with "eka" as "total", "one", "unitary and contracted with "tattva" or "principle", "nature", "essence" or "truth" so the "Inclusive Nature of the Heartmind". "Śrī" may be understood as the iconographic "glory" that is the halo and aura often depicted in art in many traditions as well as what is felt in truly good people in whom this heartmind or however else it is understood or codified in the various precious traditions of the World is manifest when we are open to the experience. Sometimes this holiness transforms people who are not even consciously ready for the experience. "Samtana" or continuum is both the Mindstream of which I have written about on Wikipedia as well as the the "flux" of all materiality, not even diamonds are forever as they are not timeless. I claim many of these traditions as mine simply as I am a Human in the current fulcrum of global culture, but I hold that in the system and development of human spirituality in a fashion many of these traditions have impacted on each other specifically in identifiable ways as well as indirectly in ways both known and unknown. This is what I term Systems Theology: a theology informed by Systems Theory and Cybernetics. Which is curious considering that Systems Theory and Cybernetics were informed by the Buddhadharma teaching of Pratītyasamutpāda of Śākyamuni (fl c.400 BCE).(Beauford the citation for this may be in the Permaculture Bible.)[1] The essence of the teaching understood as Pratītyasamutpāda isn't peculiar just to the Buddhadharma. The Doctrine of Flux has been associated with Heroclitus (c. 535–c. 475 BCE)) by Plato (428/427 – 348/347 BCE) and Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) as affirmed by Craig (1998: p.694).[2] It is written with no other purpose than this is of interest and of value to me and though I entertain that very few would find it of value, it is written as an offering to my Human family. It makes me feel that Humanity and I as a part of that class of sentient beings have a purpose even if my experience of my present generation and times is one of inanity, selfishness, cruelty and isolation from true intimacy and love with ourselves, each other and our environment and manifold living beings. This is understood as terror.

This terror is not new and I have no delusions of a once-upon-a-time Golden Age yet I have a real appreciation of how significantly the Human cultures are progressing in terms of their spirituality, inclusion and heartfulness which is being brought into line with material prosperity which is yet to be extended to all. I have no particular interest in esotericism and secret knowledge in truth. I have no particular interest in the exclusivity of such traditions even though many such traditions have been areas of my protracted study, contemplation and meditation. "Inclusive" is a practical, pragmatic and ideological inclusion. The living world is both beautiful and terrible, often simultaneously. Humans partaking of this beauty and terror are in my experience more terrible than beautiful. Beauty is understood as heartfulness. "Nature" may be understood as at once the fullness of our potential a well as actuality. "Reflexive apperception" will be dealt with throughout the work if the reader is aware and attentive of their presence in the experience of reading this work as well as specifically in due course and it is implied in the title by the material of the ankusha being "ivory" and in "svasamvedanam". The "ankusha", the "elephant goad" or "elephant hook" is chosen for personal, historical, meditative, inclusive and iconographic purpose and edification. As a practical tool of human endeavour it has roots in the "goad" of Egyptian iconography. Though it may be pereived as a tool of subjugation and domination this has both appropriate and inappropriate applications and employment. It is a metaphor for directing focus, attention and endeavour.

Nonduality

[edit | edit source]"Nondualism", "nonduality" and "nondual" are revisionist terms that have entered the English language from literal English renderings of "advaita" (Sanskrit: nondual) subsequent to the first wave of English translations of the Upanishads commencing with the work of Müller (1823 – 1900), in the monumental Sacred Books of the East (1879), who rendered "advaita" as "Monism" under influence of the then prevailing discourse of English translations of the Classical Tradition of the Ancient Greeks such as Thales (624 – c. 546 BCE) and Heraclitus (c. 535–c. 475 BCE). The first usage of the terms are yet to be attested. The English term "nondual" was also informed by early translations of the Upanishads in Western languages other than English from 1775. The term "nondualism" and the term "advaita" from which it originates are polyvalent terms. The English word's origin is the Latin duo meaning "two" prefixed with "non-" meaning "not". Wiktionary (May 2010) ventures the etymology and offers a definition of "Nondualism" thus:

- Etymology: derived from the translation of the Sanskrit term अद्बैत 'advaita', "not two".

- Noun: The belief that dualism or dichotomy are illusory phenomena; that things such as mind and body may remain distinct while not actually being separate.

Transpersonal Psychology

[edit | edit source]Caplan (2009: p.231) conveys the genesis of the discipline of Transpersonal Psychology, states its mandate and ventures a definition:

"Although transpersonal psychology is relatively new as a formal discipline, beginning with the publication of The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology in 1969 and the founding of the Association for Transpersonal Psychology in 1971, it draws upon ancient mystical knowledge that comes from multiple traditions. Transpersonal psychologists attempt to integrate timeless wisdom with modern Western psychology and translate spiritual principles into scientifically grounded, contemporary language. Transpersonal psychology addresses the full spectrum of human psychospiritual development -- from our deepest wounds and needs, to the existential crisis of the human being, to the most transcendent capacities of our consciousness."[3]

Subjectivity

[edit | edit source]Subjectivity as collapse of subject-object into a continuum of perceiver-perceived is a key theme in many nondual traditions as it is in contemporary perceptual theory. Subjectivity qua Consciousness is the conundrum and delimitation of the Human Condition.

There is no God, as I was taught in youth,

Though each, according to his stature, builds

Some covered shrine for what he thinks the truth...

There is no God, but we, who breathe the air,

Are God ourselves and touch God everywhere.

An extract from Sonnets (1915) of Masefield[4] (1878-1967) and I entreat my reader to please be gender inclusive rather than exclusive whilst reading it. There be Theism in Pantheism be under no illusions!

Human Condition

[edit | edit source]- "Sweet are the uses of adversity, which like the toad, ugly and venomous, wears yet a precious jewel in his head; and this our life, exempt from public haunt, finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything."

- Shakespeare -- As You Like It (2.1.13)

The term 'Human condition' has been employed at least since 1933 and I have as yet been unable to establish the first attested usage. Like "nondual" and its inflections, it may not as yet be documented. We each know what constitutes the human condition but often culture conceals it from us. I will state it simply here. We are an individual, no-one is identical not even an identical twin. We are in general socialized within a society of individuals, some with similarities some with dissimilarities. Many groups or communities are identified and recognized due to shared similarities eg. family, location, ethnicity, trade, hoby and culture. There are good people, bad people and people of complex alignments and agenda. There are different cultures and different polities, different political systems, different judicatures and legislatures, different laws, different countries, different cultural practices, different religions and faith systems, different values and mores. As a result there are sometimes war, conflict and strife between individuals, between communities, between individuals and communities, between other species, etc. We need water, food and air to sustain life. We tend to live in a dynamic continuum of competition-cooperation. We are embedded in complex systems organic and inorganic. Many of us establish relationships with different species. We live on Earth in the Milky Way. Depending on our locality and culture we need certain kinds of clothes and shelter. For the most part we establish interpersonal relationships. We learn unique knowledge and experiences that further individuate our individuality so that no two people have the same knowledge, skill and experience set. There is the additional texture and natural drive of sexuality and the creative impulse. We use, create and modify and innovate tools and technology. We each undergo the trial of disease and the surety of death. Generally, we have the complexity of emotions, the ability of rationality, the propensity to learn. Curiously, human memory and experience is and are designed to fade. We as a class of organism have a fractal ordering: five sections (four limbs and head) that for the most part branch into five sections (fingers and toes). We as a species tend to perceive our experience in similar ways but there are marked divergences and varietal differences. There are various rites of passage, many with celebrations and festivities. In sum, the human condition is a complex.

Embedded narrative

[edit | edit source]The classic model of the embedded narrative is the Arabian Nights wherein Scheherazade narrates stories embedding narratives to enthrall a King and thereby forestall her death. Scheherazade as the principal narrative voice, conveys narratives in complexities sometimes to the order of eight embedded narrative levels. Though the different narrative orders are discreet they bleed into one another and reflect and refract one another through various literary devices. The usage of "embedded narrative" in this investigation of nonduality partakes of this as each thematic section is an embedded narrative but the denotation is more purposeful in this context. I employ the term with its broad usage within critical theory: every text is embedded in a narrative as it too holds embedded narratives. It is the discourse of deixes, that a text as a technical term in critical theory (eg. picture, song, book, house, etc., indeed anything which conveys meaning) always points within itself, out of itself and other texts point to it by their very nature as texts: intertextuality as an interpermeablility. Any spiritual tradition worth its salt must grapple with these themes of beauty and terror. It is my understanding that the most profound, practical and beautiful wisdom traditions of the World are increasingly understood as "nondual" traditions. To live in this world we must deliver terror as a daily matter of course as plants and animals are living. If we truly need to deliver terror be heartful in so doing, this is honourable pragmatism.

Ideology and discourse

[edit | edit source]- There are more things in Heauen and Earth, Horatio,

- Then are dream't of in our Philosophy.

- ~ Hamlet Act 1. Scene V, Shakespeare

'Open Discourse' is a technical term employed in discourse analysis and Sociolinguistics which is contrasted with 'Closed Discourse'. The concept of open and closed discourse is associated with the overlay of open and closed discourse communities and open and closed communication events. Key to open and closed discourse is access to information, equity of access, open access, quality of discourse and mechanisms and modalities of discourse control: overt, covert, implicit and incidental. As a conceptual filter and cultural construct, ideology is a function and mechanism of discourse control. Channel and signal of communication event and register of communication control discourse and therefore, determine degree of social inclusion and social exclusion and therefore, efficiency of communication event. Open and closed discourse operate on a continuum where absolute closure and complete openness are theoretically untenable due to noise in the channel. Nature of channel, signal, code, replicability, recording, transmissibility, cataloguing, recall or other variable of a communication event and its information control and context of transmission-as-event, impacts on its entrance into open discourse; where open discourse is sustained discourse.

Van Dijk (c.2003: p. 357) holds that:

"Although most discourse control is contextual or global, even local details of meaning, form, or style may be controlled, e.g. the details of an answer in class or court, or choice of lexical items or jargen in courtrooms, classrooms or newsrooms (Martin Rojo 1994).[5]

Ideology as discourse control is very important for awareness in the human as it constitutes a conceptual and perceptual filter of experience.

Acknowledgements

[edit | edit source]

This exploration of nonduality as critical discourse analysis is founded upon the Nondualism article at Wikipedia, an article significantly improved by me (circa May 2010). But there are differences of opinion about the quality of my edits and contributions not to that article in particular but whether I have actually improved Wikipedia at all. After being linked with cults-in-the-pejorative, a baseless assertion mind you, I named the demon of my somesay-peers "bland stupidity" as was my experience of the them "the Mob" in question. By grace, I am not constrained in this Wikimedia Project so I will continue here presently. This work as declared above, was founded upon the work of others and their contributions may be ascertained by mining the History Tab at the appropriate page cited. I thank them for their contributions. I have left Wikipedia for the time being due to a Mob hiding behind Wikipedia's noble ideal of consensus. Unfortunately, consensus is flawed for very similar reasons as the charge made by classical and contemporary critiques of Democracy. In general, an individual cannot avail against an unfavourable Mob. Might and numbers are not necessarily right. Hence, I will continue my discourse here. This is excellent, as here I may critique my sources with my own voice and be more creative than I may be by the conventions of an Encyclopedia. It is not as immediately discoverable as Wikipedia, but Wikiversity is thoroughly indexed in time.

Now discourse necessitates a dialectic or a debate, whether this discourse happens as a verbal or textual dialogue or otherwise is irrespective. I also wish to associate the dialectic of scientific method: hypothesis, antithesis, synthesis. Where the synthesis as product in turn becomes a hypothesis and the refinement is ever-set in motion. A girlfriend of mine advised her Mother said a fact is a bubble in a spirit-level and this metaphor conveys a continuity of refining. These are all analogues of nonduality. Synthesis as monism is just nonduality from a different perspective.

"This historical pattern - famously redeployed by Mark - involved the idea of historical progression by contraries. A first condition - hypothesis - begets its opposite, or antithesis: a reaction against the first condition. From these emerge a third: a synthesis of the first two. As this synthesis fulfils itself it begins to show the germ of its own opposite, and the pattern is repeated, slightly differently. Hegel himself envisaged this chain-sequence as being ultimately circular."[6]

It most definitely is circular when viewed in two dimensions but is more appropriate when the model is transported into three dimensions and become spirallic such as the nautilus shell and an unfurling fern frond, which both follow the Fibonacci sequence famous in sacred numerical lore. And this both introduces and necessitates a discussion on Rose Windows and Sacred Geometry.

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Invocation

[edit | edit source]

Fauteux (1993: p.1) discussed the iterating dialogue of Freud and Rolland that yielded what became known as the 'oceanic experience'[7]:

Some people will take offense at the suggestion that religious experience is a return to primitive psychological processes. Others will say it is obvious. Their differing views can be traced back in this century to the debate between Sigmund Freud and the French philosopher Romain Rolland.[8]

Albrecht (2007: p.51) holds:

"At the basal region of your brain, your spinal cord enlarges to form the medulla oblongata, and above it a bulbous structure called the pons, two structures that regulate and control the most primitive aspects of life: breathing, heartbeat, arousal, and primary motor control. This portion of the system is sometimes called the brainstem, considered by scientists to be the most ancient part of the brain, evolutionarily speaking. We share this primary type structure with reptiles, birds, and probably with the dinosaurs."[9]

Dharmic Traditions: Ekayāna of Dharma

[edit | edit source]Seeing the truth beyond the words of the following quotation through the employ of essence-function and the pragmatism of the Buddhadharma, the concepts of 'God' and 'soul', etcetera, may be provisionally engaged as upaya. Underhill (1911: unpaginated) in her Preface to the Twelfth Edition of her seminal Mysticism[10], drawing on the work of Von Hügel, conveys the "freedom and originality", (indulging in a tangential aside, both technical terms in Dzogchen that will be explored later in this text) that arises from the interpenetration of 'institutional authority' and 'mystical authority' of direct experience, states:

First, that while mysticism is an essential element in full human religion, it can never be the whole content of such religion. It requires to be embodied in some degree in history, dogma and institutions if it is to reach the sense-conditioned human mind. Secondly, that the antithesis between the religions of “authority” and of “spirit,” the “Church” and the “mystic,” is false. Each requires the other. The “exclusive” mystic, who condemns all outward forms and rejects the support of the religious complex, is an abnormality. He inevitably tends towards pantheism, and seldom exhibits in its richness the Unitive Life. It is the “inclusive” mystic, whose freedom and originality are fed but not hampered by the spiritual tradition within which he appears, who accepts the incarnational status of the human spirit, and can “find the inward in the outward as well as the inward in the inward,” who shows us in their fullness and beauty the life-giving possibilities of the soul transfigured in God.[11]

In declaration at the outset I have a strong sense of God qua the Ground-of-Being as an interpenetration of Personalism (Saguna Brahman; Samboghakaya) and Impersonalism (Nirguna Brahman; Dharmakaya). I do not consider one of these to be ascendant or primary. This does not confound my understanding of theurgy and my working with archetypes and tutelary deities as the imaginary friends of childhood writ large for spiritually developmental adulthood. To the untrained and uninformed sensibility, the wrathful yidam of Buddhism and Bon sadhana appear as demons and monsters, this quotation of Nietzsche's informs the interpenetrating reciprocity of iṣṭhadevatā and sadhaka, and the coalescence of the two kinds of Śūnyatā:

He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.

Kipling's 'The King's Ankus'

[edit | edit source]

As a child my exploration of the Dharma may have commenced with the Ankus. This may be a romantic notion, and the romance or rasa of 'reptilian-brain' (technically the Basal ganglia) endocrine feelings and sentiment or electrico-chemical sediment or instinctive hormonal-pulse in the bodymind system of the human mindstream are important in the Dharmic Traditions but more on that later; but the Ankus is the first iconic cultural artifact from the Dharmic Traditions that I remember, remembering. The Dharmic Traditions comprise the Sanatana Dharma, Sikha Dharma, Buddha Dharma, Jaina Dharma, etcetera. Historically, this is what these traditions were known as in their indigenous tongue where 'tradition' is an English gloss of words in the Sanskrit lexicon such as 'parampara'. Now this is somewhat lauding the Sanskritic great and learned tradition but many of the other indigenous tongues have worthy 'dharmic' literatures in their own right and rite. The semantic field for 'tradition' in the indigenous Dharmic tongues is and are vast. I prophesy a great frank female French scholar from without the bastion, auspice or ken of the academic ivory-tower in the fabled not too distant future will unpack these for the discerning English reader. In Western academic scholarship the cult of Grecian or Hellenic -Isms has superseded "Dharma" and rewritten them namely as Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism etcetera which is flawed and unfortunate and betrays that the traditions are fundamentally systemic and related. This is the principal reason why I prefer the rubric "Dharmic Traditions". This will become the standard.

Now back to the discourse of the Ankus. I first remember sighting and herewith cited in the movie, Jungle Book (1942) originally black and white trailblazing 'merchant ivory' film noir, later doctored, polychromatically stained, technically technicolored. It is downloadable from The Internet Archive, I need to watch it again and take detailed notes. But then in truth I need do nothing and am not required to do anything as 'knowing' arises naturally and unbidden in my mindstream. At the Positive Living Centre I happened upon the The Second Jungle Book of Kipling's in print and by the grace of goddess Serendipity it had this preeminent story enfolded within it. I mention the Positive Living Centre sited in Melbourne Australia as they feed me, an Avadhut. Feeding an Avadhaut is THE most holy activity that can traditionally be done in the Dharmic Traditions. Importantly, ANY Avadhuta is sacred in ALL the Traditions. An Avadhuta transcends the tradition even whilst they are positioned within it. Now the Positive Living Centre are not formally a part of the Dharmic Traditions but wise Indian women get their children to brush my corporeal form. Ancient traditions are living traditions and are invested in me. I mention them as I honour them and they do good work. Some people consider me egoic and prefer a 'teacher' less learned but more lauded which just offsets their institutionalized stupidity and penchant for the cult of prestige which I identify and defame later. The Avadhaut are fundamentally dejected and neglected and it is from this as much as anything else that is the origin and wellspring of their power. That and the sanctity, trial and burden of being set apart and singled out. The archetype of the scapegoat of which the Avadhaut partakes has an ancient heritage more significant than the quasi-historical sacrifice of Christ's the 'christos' or 'annointed-one' somesay circa 2000 year odd blood-rite. I could frame this now but it is not required and is easily discoverable. Let us keep to the order of ceremonies and the matters at hand.

Many consider Second Jungle Book superior to the first and that the King's Ankus the jewel of the suite of Jungle Book stories and amongst Kipling's greatest works. I knew it would naturally appear in my lifepath when timely. The amazing thing is, in the movie the Ankus is not ivory, but in the story a part of it is and it is bejewelled with a magnificent ruby and attendant turquoise. I named this exploration the Bejewelled Ankusha of Ivory before I knew that the original Kipling ankush from the short-story was ivory. That has profound significance for me as my intuition in my journey has been absolute. The timeless quality of the ivory Ankus of this work will be made apparent in time. The Kipling story gives the appellation "blood drinker" to the Ankus which brought blood blessing of Heruka clearly to mind. The mind is well-blooded, let us not forget. The English term 'to bless' is etymologically rooted in both 'sacrifice' and 'blood'. Ancient wisdom is encoded in etymology and semantic fields. The ivory nature of the Ankus in this work is key and that it is in Kipling's and other evocations of this tale betray that he either had a keen appreciation of the traditions of the Dharma or that he was accessing the Akasha or that I am attributing qualities to his work that are not there. The sum may be true, none or some. The Introduction to the World's Classics edition Oxford University Press (1987) by W. W. Robson states that this story is the best, the most accomplished out of both Jungle Books. For a time Kipling was considered one of the greatest writers of the language by both scholars and the general reading public, well so Robson relates. That the Ankus is ivory powerfully reinforces my appreciation of my intuitive guidance, the 'blessing' (Sanskrit: adhishthana) I had prior, during and subsequent to my entwinement, the pointing out instruction to the primordial nature of mind by the naga and that "we be of one blood ye and I" of all sentient beings and phenomena, lifebood, whether breathing, or living, sentient or falsely considered inanimate. Yes, I am a pantheist, panentheist and animist but not just delimited and compromised by these, but for me stated simply, there is nothing that is not animated by the grace of 'creative intelligence' (Sanskrit: prakriti). If this confounds you, Sanskrit and the Dharma just embrace the intention apart from the tradition, imbibe the salience beyond the measured letter of the words.

An ancient paradigm as the present darling of the Academy'

[edit | edit source]Nondual can refer to a belief, condition, theory, practice, or quality. The academic disciplines that study Nondualism in its spiritual permutations and cultural evocations are Transpersonal Psychology and the Anthropology of Religion and Theology amongst others. Though nondualism proper has historically been glossed as "monism" and its variants as "qualified monism" with which it may appropriately or inappropriately be conflated, the nomenclature "nonduality" is now a pervasive paradigm in Western scholarship throughout diverse academic disciplines. Importantly, such paradigms that transcend either/or constructions are pertinent given Quantum superposition theory and the models of light as simultaneous wave-particle constructions that we determine through the intent of our subjectivity.

Traditions of monism according to premier contemporary discourse invested in such works as McEvilley (2002) for example where it should be stated the absence of the term "nondual" and its inflections are conspicuous. Well it has been employed in relation to the Upanishads and Advaita Vedanta but not elsewhere. Maybe, this is to be lauded. That is yet to be determined though discourse analysis. I searched in the parts of the texts that are discoverable in Google Books and you may do so as well. Monism is to be found or even more adroitly, we now perceive its traces in ancient Egypt, ancient Persia and ancient India; in the Classical traditions of ancient Greece and ancient Rome; in several major world religious traditions; and indigenous traditions such as the Navajo; in a number of philosophers such as Martin Buber, Hans-Georg Gadamer[12] and Jacques Derrida[13], and various mystics within orthodox and heterodox traditions or arising outside of any tradition, amongst others.

Michaelson (2009: p.130) writes:

"Conceptions of nonduality evolve historically."[14]

Present "darling" of the "Academy"? So many "spiritual" books, teachers, traditions and texts tout "nondual" of late. I venture it is often ungrounded, unspecified and rarely made clear exactly what is nondual. Academy? Those who can spell and in whom are invested prestige, a prestige attributed. Is such prestige well founded and sound? We each have to determine that for ourselves.

Why is the paradigm of nonduality so valuable? Well said simply, it is very difficult with certainty to determine where any entity ends and where any entity is or where any entity begins or even to define what an entity is. Defining anything is problematic in truth. Do you end at your skin? At your range of sight? At your range of hearing? At your range of experience? At your range of knowledge? At your social-interactions? At your last breath? At the last beating of your heart? Where do we begin in the sense of the personal 'entity'? At the union of zygotes? At our first breath? At our first heartbeat? At birth? When your eyes first focus? Contemplate it. Do we begin with the origins of DNA? The origins of the Universe? When contemplating the nature of your perception as you are aware of it be aware of notions such as qualia? What is the universal if any in an entity such as a dragonfly perceived by a human as different to a dragonfly perceived by a canine as different to a dragonfly perceived by a bird? Unpacking qualia, colour, in the last or final analysis is determined by subject yes? Not by object or atmosphere nor by refraction of light and this is just one example. The subjectivity interpenetrates and informs the perception event, the cognition event of that perception event, and then the attribution of meaning to the said wave of embedded processes. Maybe there are no events but a seamlessness? It is counter-intuitive, but it may be affirmed with certainty *chuckle* that the subject and the object are not distinct.

A note on sanctity and profanity, a fun profundity

[edit | edit source]Since early youth I have been a person (and we have already established the problematic notions of persons and entities) who goes into altered states of consciousness with minimal cue. As a child I called it phasing. I went into such a state when I wrote the first version of the Trance article on Wikipedia which I created. The content emerged from me spontaneously as the fruit of a lifetime of research and endeavour. I pray that it will be appropriately cited in the years that come.

This phasing is not necessarily day-dreaming, there is no fancy. There is just union. One of my favorites as a child was gnat-vision where I would be entranced by the Darśana of the pulsing chaotic-order of a sphere-swarm of gnats. I also have been unable to be hypnotized in the "formal" sense though my Mother by birth but not by quality tried and tried. What has that got to do with anything? I am not going to explain everything. I affirm with no prejudice and with no fear that I am as holy and as profane as any other human being that has ever graced our world in the full history of this gracious Blue Planet Earth. That said, my style of profanity though wanton and sensual has never been evil. Sensuality is a source and wellspring of spiritual power. Indeed, a fun profundity. This comely import will be cumulatively nailed and nailed with an even and decided precision as a matter of course in the relentless ebb and flow of interpenetrative, embedded discourse. There is a folk saying within the International Dzogchen Community that a Dzogchenpa's realization is determined by the number of sexual contacts/partners they have accrued in their life-path. This is amplified with the fecund Nath (where the end phoneme is an aspirated T as there is no "th" sound as in English "path" within the Sanskrit garland of phonemes) and the ancient traditions of the Avadhaut. Let us name the demon of puritanical nay puratyRRRanical tyranny exactly that. Forget what you may have read or have heard, holiness in all its evocations in ancient Mother India has never been the sole domain of the bodies-sexed-male, that is if we qualify the Vedic Agnihotra and Purohit Brahmanical rites, but throughout the manifold diversity for the most part our blessed women and shining third-gender were evident in the field of sacred play. Sanyassin were of all genders and their attributed continence qua celibacy is of recent construction and not universal in the manifold Sanyassin traditions. That said, even in the ancient Indian tradition sanctity was not the sole domain of any particular aspect of the Varnashram Dharma or without. "Nath", as different to the Sampradaya, is simply a Sanskrit term for a "master" of multiple spiritual traditions. Something curious happens when you are a master of multiple traditions. What do you intuit that may be? Many of the ancient Avadhaut texts have not even entered English discourse. Why? Prudish scholars etic and emic and they have been lost to the archives of history. This will change. Avadhaut is the plural for Avadhut. The wonders of nondual praxis!

A Swarm Of Gnats

Many thousand glittering motes

Crowd forward greedily together

In trembling circles.

Extravagantly carousing away

For a whole hour rapidly vanishing,

They rave, delirious, a shrill whir,

Shivering with joy against death.

While kingdoms, sunk into ruin,

Whose thrones, heavy with gold, instantly scattered

Into night and legend, without leaving a trace,

Have never known so fierce a dancing.

Hermann Hesse as rendered in English from the German by James Wright[15]

Etymology and an introduction on the fly

[edit | edit source]I have been unable to source the first attested usage of "nondualism", "nonduality" and "nondual". They may as yet be undocumented. But I hold that they are revisionist terms that have entered the English language from literal English renderings of "advaita" (Sanskrit: nondual) subsequent to the first wave of English translations of the Upanishads commencing with the work of Müller (1823 – 1900), in the monumental Sacred Books of the East (1879) which he edited, wherein "advaita" was rendered as "Monism" under influence of the then prevailing discourse of the Classical Tradition of the Ancient Greeks commencing with the "monism" of such as Thales (624 – c. 546 BCE) and Heraclitus (c. 535–c. 475 BCE). Muller and many of the other learned and lettered of those times were versed in many languages and Greek and Latin were mandatory to be considered "cultured" and "finished". I have never read any of my forebears state that Indian literature, wisdom and philosophy, its very "memes", entered English discourse by way of the lens of the Classical Tradition and the cultural mores of the Victorian society then prevalent. But this is being stated by me clearly and stated here. Hence, the necessity of revisionism. Whether stated clearly or documented, this has been happening constantly. Knowledges and disciplines constantly interpenetrate and redefine and mutually inform and qualify. This complexity is now happening at a rate neverbeforeseen by our Humankind through facility of the Internet and the dawn of open discourse as accessible discourse. Finally, the manifold discourses are being made available to the general populace most of which are not interested or even aware that they are becoming available. Traditionally, by whom was information mediated? Contemplate that. Contemplate agendas and embedded values. The "Orient" and its perceived cultural tokens were considered wealthy and therefore prestigious. Note, the unholy constructions of the Other which the discourse of nondualism nails as unfounded. I will talk on the discourse of prestige later. I am writing conversationally. I venture it is more intelligible to most of my potential audience to employ such a voice and register. I mention discourse often don't I? I will explain the value of discourse analysis very soon.

Knowledge as part of the human condition is always grafted upon knowledge already evident. Study the history and mechanism of human metaphorical construction and my point will be somewhat clear. The human brain is made in such a way, that is in the way that we construct metaphors ~ an ancient foundation upon which have been established annexations. We construct as we are constructed. Curious, yes?

My conjecture upon "nondual" and its inflections may or may not be correct, but it is better than any source I have yet encountered. That is saying something. We have to build knowledge somewhere and I have declared the foundations unsure. This entails a very important point, knowledge is never factual. What we call facts are arbitary units of meaning founded upon other units of meaning. In truth facts are very unstable and this is clearly evident when reading a textbook in any discipline of over 100 years ago. The first usage of the terms are yet to be attested. It is highly probable that the English term "nondual" was also informed by early translations of the Upanishads in Western languages other than English from 1775. The term "nondualism" and the term "advaita" from which it originates are polyvalent terms. The English word's etymology is the Latin duo meaning "two" prefixed with "non-" meaning "not".

Language is functional and creative, purposeful. There are no true synonyms in any natural language. If you are unsure what that means contemplate it. I tender there is sound wisdom in that point, sage. "Nondual" is neither especially aesthetic nor creative. That is clearly evident yes? Hence, I declare it to be functional. New terms enter a language for many reasons; for example, technological change and cultural appropriation and necessity, amongst others. New terms are often memes that are valuable such as loan words. I venture why would the English language have even had the construction or necessity for the term "nondual" when there are so many other attested, established, beautiful terms already in the historical lexicon. Neither "nondual" nor its derivatives are available in my Shorter Oxford on Historical Principles; hence, they are new words. I love a sound point of entry.

What is nondual exactly?

[edit | edit source]Pritscher (2001: p.16) attributes a salient view on nondual realization to Loy (b.1947), an author of a work on comparative philosophy of nondual theologies i.e. Loy (1988)[16]:

"According to David Loy, when you realize that the nature of your mind and the [U]niverse are nondual, you are enlightened."[17]

The experience of a human being's outer world, that is the sum and suite of experience perceived 'outside' their body with the five senses informs ones interiority, one's mind. That said, similarly within the imaginal and cognitive realm of mind when we conjure or envision a visionary or imaginal experience with eyes shut and ears sealed to external stimuli, we may still employ all five senses, e.g. we remember or imagine an event that entails the five senses through the faculty of our mind. According to our faculty for example, we hear and perceive the imaginal as a 'real' experience in mind. Our mind doesn't discriminate either between an internal or external event: we salivate the same if we imagine a delicious meal as if we perceive one that is not imaginary. Interiority of thought and exteriority of thought in relation to the projection and reach of the sensory apparatus are conventions that each human being has by and large been calibrating since they first began to walk, see, touch, hear and taste/smell. The calibration becomes a living convention and we forget, never know or denigrate this knowledge and its wisdom and value. A wonderful aside is taste and smell, they are not different senses but by convention in English we construct them as different sensory domains.

In reprise, one's interiority consciousness one's subjectivity is a reciprocity with that which is exterior to our imaginal realm, the ontological separation of interior and exterior though counterintuitive is an illusion of the convention of our body-senses-mind calibrated or embodied experience within the bodymind system. Our interiority structures the interpretation of our experience. Our exterior socialization and experience in the world colour our interiority. Our consciousness events are determined by our experience of the world, coloured and flavoured by our cognitive propensity and sensory facility. How similar is the cognitive propensity and sensory facility of the Human?

The Mind and memory as a reservoir for objects of experience and reflection upon living embodied experience is our Universe, that is we have bodily calibrated conventions that are mental constructs, formations or ideations, that are qualified and constituted by subtle names and formative patterns. The Sanskritic tradition knows these as 'names-and-form' (namarupa). For the subjective human, our respective Universe is the Mind: in the most broadest denotation Mind and Universe mutually evoke and qualify. The Universe denotes the totality of the external world that may never be experienced in sum, an unknowable and an indefinable. Defining any object in a subjective or cavalier attempt at objective view is fraught with insurmountable obstruction. Defining anything definitively is futile. This is counter-intuitive as well but contemplate it. Where does something begin and end, what is its context what are its processes what is universal about it independent of our experience. An awareness of such complexity and unknowability and undefinability may truly awaken a person who has lost their sense of awe in their lived experience. The world is alive with mystery wherever we look but we close mystery by explaining it away, often very unsuccessfully.

Our Universe is our experience and knowledge of it. Therefore, in no uncertain terms Mind and Universe thoroughly interpenetrate. Interpenetrate is a particularly Chinese flavoured nondual language. This interior-exterior imagination-actuality isn't some metaphysical hocus-pocus some wordplay with no value or referent in the world: make no mistake. Is it possible to have an interior thought of something that has not been established from the building blocks of external experience? If I change my understanding of a concept, that change might not necessarily change the materiality the physical fabric of my World or of THE World as such but it changes my response, interpretation, knowledge and value of that materiality and physicality. Due to our subjectivity if we change our perception of our experience, our experience changes necessarily. What we understand as material and physical substance is problematic from the perspective of Human consciousness, as our experience is fundamentally subjective. Our subjectivity is the great qualifier of all our experiences 'in' the World. Where the 'in' really happens in the mind. This nonduality of the perceiver and perceived of that which is being apprehended by the apprehending sentient being is key to many nondual traditions and it is through this nonduality that other nondualities are mediated. Indeed, it may be due to the very nature of the nonduality of perceiver-perceived that all other types of nondualities in our experience of the World are evident.

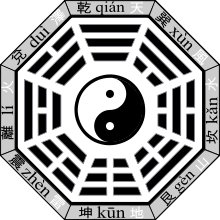

Loy (1988: p.3) contrasts his view of the historicity of nonduality in some of its evocations in the experience of the peoples of The East and The West as follows:

"...[the seed of nonduality] however often sown, has never found fertile soil [in the West], because it has been too antithetical to those other vigorous sprouts that have grown into modern science and technology. In the Eastern tradition...we encounter a different situation. There the seeds of seer-seen nonduality not only sprouted but matured into a variety (some might say a jungle) of impressive philosophical species. By no means do all these [Eastern] systems assert the nonduality of subject and object, but it is significant that three which do - Buddhism, Vedanta and Taoism - have probably been the most influential."[18]

Nelson (1951: p.51-52) cites Radhakrishnan's The Principal Upanishads (1953) where Radhakrishnan renders a passage of the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (verse 1.4.16) which demonstrates a theme that one becomes transpersonally identified with, or nondual to, or develops qualities associated with that to which one is engaged, worships or holds holy and though it is translated with a male pronominal it may be understood as not being gender-specific:

"Now this self, verily, is the world of all beings. In so far as he makes offerings and sacrifices, he becomes the world of the gods. In so far as he learns (the Vedas), he becomes the world of the seers. In so far as he offers libations to the fathers and desires offspring, he becomes the world of the fathers. In so far as he gives shelter and food to men, he becomes the world of men. In so far as he gives grass and water to the animals, he becomes the world of animals. In so far as beasts and birds, even to the ants find a living in his houses he becomes their world. Verily, as one wishes non-injury for his own world, so all beings with non-injury for him who has this knowledge. This, indeed, is known and well investigated."[19]

Transpersonal psychology

[edit | edit source]Theriault (2005) in a thesis explores comparative non-dual experience and the psycho-spiritual mechanisms that bring the awareness about.[20] Lewis (2007) in her thesis explores a number of specific women's experiences on their journey to wholeness and healthfulness in the nondual path of Tantra post-sexual trauma and identifies common themes.[21]

Nondualism versus monism

[edit | edit source]The English usage of the term "monism" is first attested in the work of Wolff (1679 - 1754) as relates Hegeler (2009: p.165):

The terms monism and dualism are not yet two centuries old; the former was invented by Christian Wolff as a contrast to- the latter, which, according to Eucken, appears first in Thomas Hyde's book "Historia Religionis Veterum Persarum," 170o, as a designation of Zoroaster's religion. In the same sense, dualism is used by Bayle and Leibnitz. But Wolff applies the term generally to any theory that reduces existence to two independent substances, while monism to him is that doctrine which takes the unity of existence for granted. Wolff rejects monism and classes himself among the dualists.[22]

So it is useful to note that the construct of the term "monism" was established at its outset in a relationship of mutual exclusion with Zoroastrianism which was in turn understood as an example of "dualism".

The Greek language has two words for "one": hen and monos. Hen is the numerical "one" that precedes two, three, and so on; monos means one alone, unique, or the only one, as in the term "monotheism."[23]

The philosophical concept of monism is similar to nondualism. Indeed, the terms are used as congruent by many scholars. Some forms of monism hold that all phenomena are actually of the same substance, Substance Monism, where the substance is the substratum. Other forms of monism including Attributive Monism and Idealism are similar and sometimes overlapping concepts to some nondualisms. Nondualism proper holds that different phenomena are inseparable or that there is no hard demarcation separating them in the final analysis, but not that they are the same or identifiable. The distinction between these two types of views is considered critical in Zen, Madhyamika and Dzogchen, all of which are nondualisms proper. Some later philosophical approaches also attempt to undermine traditional dichotomies, with the view they are fundamentally invalid or inaccurate. For example, one typical form of deconstruction is the critique of binary oppositions within a text while problematization questions the context or situation in which concepts such as dualisms occur.

Daniélou (1907 – 1994) opines that "nondualism" is "dangerous" as it "rests" on "monism":

"The term "nondualism" has proved, in many instances, to be a dangerous one, since it can easily be thought to rest on a monistic concept. The Hindu philosophical schools which made an extensive use of this term opened the way for religious monism, which is always linked with a "humanism" that makes of man the center of the universe and of "god" the projection of the human ego into the cosmic sphere. Monism sporadically appears in Hinduism as an attempt to give a theological interpretation to the theory of the substrata.... Nondualism was, however, to remain a conception of philosophers. It never reached the field of common religion."[24]

Though I can't speak for Daniélou and say definitively why this is "dangerous". I understand this argument would be the position of absolute Dualists, for example Madhvacharya (1238-1317), who are reputed to have held an inseparable distinction between a supreme creator and the created, and would find monism qua advaita abhorrent. My personal view of duality and nonduality as a nondual system and mutually iterating is informed by Ramanuja (1017 – 1137) as not only is it the most practical way of being in the World but also is commensurate with my living experience and realization. I hold that pure Advaita is perceiving from the Absolute Truth whereas pure Dualism is perceiving from the Relative Truth. None are right nor wrong if their heart is filled with love as they can abide in Mystery. I don't necessarily embrace all the bells and whistles of any of these traditions as theology does not stay fixed in time. I should also state here that my direct experience of Absolute Truth is that which partakes of Dipolar theism and this is the rationale why we all incarnate so that the unmoving is moved through us. My understanding of "Dipolar theism" is that deity is the nonduality of Being-and-Becoming. "Us" is to be understood as any not in the position of the Absolute. That said another way, the manifold iterate the unmanifest; the unmoving enjoys the becoming of the play of diversity. There is a reciprocity between the Two Truths.

Macranthropic Monism

[edit | edit source]McEvilley defines and discusses Greek/Latin Macranthropos and Greek Pantheos as related conceptions. Macranthropos is a contraction of the Greek and Latin prefix "macro-" meaning "large" and "inclusive" and the Ancient Greek "anthrōpos" or "ἄνθρωπος" meaning “man, woman, human being”). Pantheos is a contaction of Ancient Greek "πᾶν" or "pan" meaning "all" and Ancient Greek "θεός" or "theos" meaning "deity, a god, a goddess, God". Pan is also the fecund Ancient Greek deity of Nature and it is from the construction Pantheos that English owes the term Pantheism. McEvilley constructs an adjectival declension of "macranthropos" as "macranthropic" and employs it to qualify monism. The first attested usage I could find on the Internet for a declension of "Macranthropos" was "Macranthropy" in the revised and enlarged Bollinger edition(1964: p.408), an English rendering by Willard R. Trask of Eliade's (1951)[25] seminal work from the French and it is contextualized thus:

"The homologizations between the human body and the cosmos, of course, go beyond the shamanic experience proper, but we see that both the vrātya and the muni acquire macranthropy during an ecstatic trance."[26]

To extrapolate further, Macranthropos is an inclusive anthropomorphism of all-that-is (and the is-not in the sense of space-as-container) as a "Cosmic Person" whereas Pantheos doesn't necessarily though may anthroporphize the totality of all-that-is (and the is-not in the sense of space-as-container), but this totality is understood as a unitive deity that may be intuited as being without human attributes and this abstraction is important. This is-not aspect as a compliment of all-that-is is implied in a conception of totality but is rarely explicitly stated; making this explicit clarifies the possibility of a substantive conception or material bias. This all-that-is & is-not substance as unity is the monad, the very stuff of "Substance Monism" (which includes non-stuff) which may be further abstracted or qualified with attributes according to human conception. In context, both Macranthropos and Pantheos are understood as the all inclusive deity. Pantheos with its makeup of "theos" denotes that it is worshipful and worthy of veneration which Macranthropos does not necessarily entail in its etymology.

It should also be stated that personification doesn't necessarily imply anthropomorphism (but may): it is in this rarefied denotation that Pantheos may be a personification but not an anthropomorphism. Some may start and make exception at this distinction and proffer how can there be personality without human characteristics? This is in part salient but also ignorant of the human capacity for metaphorical extension. Can we conceive of a possible world where personality is an attribute of the non-human? Yes, it is not a significant challenge. Indeed, it is a stock narrative device and ancient storytelling technique employed in Allegory. It may be conjectured that Humanity through its humane faculty its empathy does indeed perceive personality or attribute personality to the non-human and this may be a natural psychological attribution if not vain fancy. But this may also be understood as an experience or perception not as attribution; hence taking place prior to conception or the birth or forming of concepts, indeed the subtle cognition of an experience or intuition given form in language or other signification such as iconography by way of the function of metaphorical extension.

Substance Monism or Material Monism

[edit | edit source]Substance Monism stated simply where the type of monism posited is that all that is and is not (which is understood to denote a complete set of possibility and actuality) is fundamentally the same stuff or non-stuff, the substrate.

Material monism is a Presocratic belief which provides an explanation of the physical world by saying that all of the world's objects are composed of a single element. Among the material monists were the three Milesian philosophers: Thales, who believed that everything was composed of water; Anaximander, who believed it was apeiron; and Anaximenes, who believed it was air.

Thales

[edit | edit source]

Thales of Miletus (Ancient Greek: Θαλῆς) (circa 624-546 BCE) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher of the Classical Hellenic tradition.[27] According to Bertrand Russell, "Western philosophy begins with Thales."[28] Thales attempted to explain natural phenomena without recourse to mythology and mythological thinking and was formative in this influence. Almost all of the other pre-Socratic philosophers follow the lead of Thales in this endeavour to proffer an explanation of ultimate substance, change, and the existence of the World -- without recourse to mythology and mythological thinking. Those philosophers were also influential, and eventually Thales' rejection of mythological explanations became an essential tenet for the scientific revolution. Thales was also the first to define general principles and set forth hypotheses, and as a result has been given the nomenclature the "Father of Science".[29][30]

Anaximander

[edit | edit source]From Wikipedia and needs to be rewritten:

The apeiron is central to the cosmological theory created by Anaximander in the 6th century BC. Anaximander's work is mostly lost. From the few existing fragments, we learn that he believed the beginning or first principle (arche) is an endless, indefinite mass (apeiron), subject to neither old age nor decay, which perpetually yields fresh materials from which everything which we can perceive is derived.[31] Apeiron generated the opposites, hot-cold, wet-dry etc., which acted on the creation of the world. Everything is generated from apeiron and then it is destroyed there according to necessity.[32] He believed that infinite worlds are generated from apeiron and then they are destroyed there again.[33]

Attributive Monism

[edit | edit source]Nondualism versus solipsism

[edit | edit source]- I

- Know you appear

- Vivid at my side,

- Denying you sprang out of my head,

- Claiming you feel

- Love fiery enough to prove flesh real,

- Though it's quite clear

- All you beauty, all your wit, is a gift, my dear,

- From me.

- ~extract of Sylvia Plath's 'Soliloquy of the Solipsist'

Nondualism superficially resembles solipsism, but from a nondual perspective solipsism mistakenly fails to consider subjectivity itself. Upon careful examination of the referent of "I," i.e. one's status as a separate observer of the perceptual field, one finds that one must be in as much doubt about it, too, as solipsists are about the existence of other minds and the rest of "the external world." (One way to see this is to consider that, due to the conundrum posed by one's own subjectivity becoming a perceptual object to itself, there is no way to validate one's "self-existence" except through the eyes of others—the independent existence of which is already solipsistically suspect!) Nondualism ultimately suggests that the referent of "I" is in fact an artificial construct (merely the border separating "inner" from "outer," in a sense), the transcendence of which constitutes enlightenment.

Metaphors for nondualisms

[edit | edit source]"Buddhism has refined various methods to observe consciousness from the first person perspective for two thousand years. Therefore it is meaningful to bring the explanation models of Tibetan Buddhism into a cross cultural dialogue."[34]

- Jewel Net of Indra, Avatamsaka Sutra

- The World Text, Avatamsaka Sutra NB: Northrop Frye

- Blind men and an elephant

- Eclipse[35]

- Hermaphrodite, e.g. Ardhanārīśvara

- Mirror and reflections, as a metaphor for the continuum of the subject-object in the mirror-the-mind and the interiority of perception and its illusion of projected exteriority

- Great Rite

- Sacred marriage

- Marriage

- Sexual union, as well as orgasm

- Water-and-wave, Awakening of Mahayana Faith

- Nonduality of rays-of-the-sun or sunrays from the Sun, Lankavatara Sutra

- A lamp that self-illuminates as it illumines, for apperception or reflexive awareness

- A lamp and its light, Platform Sutra a metaphor for Essence-Function where Essence is lamp and Function is light[36]

Simulacra and Simulation

[edit | edit source]Baudrillard (1929 – 2007) Simulacres et Simulation (1985) seminal work in the French was rendered into English by Glaser as Simulacra and Simulation (1996) & an Internet copy may be viewed at Scribd Glaser's translation dated 1996. It is through his work that Simulacrum takes on a different meaning and especially that used in iconography by Beer (1999) which is important. This is very thematic as it links with representationalism and facticity. Facticity is the unknowable first of which the simulacrum is facsimile without original: that holy grail objective truth that the subjective never accesses, except as fabled by some nondual traditions by 'direct perception' (S: pratyakṣa) through divine grace. It should be stated here that there are different types of direct perception and this will be discussed as this is key to some aspect of nondual experience. I want to mention phantasmagoria and sky-flowers here and the City of Gandharvas and Tulpa and the famous analogies of the Buddhadharma....

Beer (1999: p.11) employs the term 'simulacrum' to denote the formation of a sign or iconographic image whether iconic or aniconic in the landscape or greater field of Thanka Art and Tantric Buddhist iconography. For example, an iconographic representation of a cloud formation sheltering a deity in a thanka or covering the auspice of a sacred mountain in the natural environment may be discerned as a simulacrum of an 'auspicious canopy' (Sanskrit: Chhatra) of the Ashtamangala.[37] perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena approaches a cultural universal and may be proffered as evidence of the natural creative spiritual engagement of the experienced environment endemic to the human psychology.

Shakyamuni employed ten traditional similes in explanation of 'phenomena' (Sanskrit: dharmas) these are known as the "Ten Similes of Illusory Phenomena" (Wylie: shes-bya sgyu-ma'i dpe-bcu) and these inform the import of Baudrillard's "simulacrum":

The ten similes which illustrate the illusory nature of all things are: illusion (sgyu-ma), mirage (smig-rgyu), dream (rmi-lam), reflected image (gzugz-brnyan), a celestial city (dzi-za'i grong-khyer), echo (brag-ca), reflection of the moon in water (chu-zla), bubble of water (chu-bur), optical illusion (mig-yor), and an intangible emanation (sprul-pa).[38]

Sumer

[edit | edit source]

Enuma Elish

[edit | edit source]- i have sourced the cuneiform and the transcription except neither of them are in unicode unfortunately...

- http://books.google.com.au/books?id=xSyxDEGcAvcC&lpg=PA4&ots=F1jWKQ9Y2b&dq=enuma%20elish%20tablet%204&pg=PA5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Egypt

[edit | edit source]"What difference is there, then, between God and primigenial chaos?"

Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Egyptian iconography and art is mesmerizing isn't it? There is a unique quality to the visual experience of it that is capturing and defining but difficult to pinpoint. Egypt iconographic representationalism is patently different to other forms of human art and cultures and is particularly recognisable in its depiction of the human form, amongst other stock representations such as feathers and papyrus-reeds, etc. In general in the ancient Egyptian visual depiction of the human form there is a multidimentional collapse of perspectives. To contemporary understanding post Renaissance Europe informed by the representations of the human form in the Classical period of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egyptians had a particular sense of perspective of the human form. As a peoples they were magnificent engineers, with feats that persist in baffling our contemporary construction methodologies but a contemporary school child of primary school age with a particular flourish and artistic skill may represent perspective and dimensionality in visual representations with more apparent sophistication that these great ancient engineers. There is a progression of the general status quo of aptitude of the Human yes?

The Egyptians ingeniously represented multidimensionality in a two-dimensional medium. A stepping stone of visual and representationalism problem-solving. Looking at the depictions of Egyptian numinous beings, we see both their shoulders and torso as though from a direct encounter, stated differently, that is a front-on view dimensionally collapsed upon legs and lower body as well as face in dimensional profile. Human perception and ability to represent that visual experience is constantly evolving. Visual representation is a metaphor for the development and iteration of the Human. We are a race in progress. The theology of the Human and their experience of Divinity and that which is Numinous is similarly a work in progress.

Nonduality as a theological paradigm has become pervasive thoughout nominally non-theological dimensions. But from a nondual worldview all that is in and of the world ever-qualifies and mutually informs as we as a species refine our appreciation of manifold interconnectivities and subtle relationships of our lived experience. I don't really have any sense of historicity or progression with Ancient Egypt and its relationship with other cultures of the Ancient Near East. I am not an expert in anything in particular and have no special knowledges, this is just a play in the experience of the Human and my reflection upon matters of interest to me. If it is of value to someone, that is a miracle in and of itself.

The rationale for evoking the experience of Egypt in the evolution of the experience of the Human and our theology I hope will be intuitively grasped by my audience. I will hint at it henceforth: the primordial waters 'mythologem' to employ a term introduced into English by Kerényi (1897 – 1973) is salient. This primordial waters motif is the mythological root of human mythological imagination that through the process of abstraction and metaphorical extension was reduced, distilled or refined to the concept of a 'material monism'.

McEvilley identifies the Hymn of Amun-Ra as the first documented origin of the idea of monism. Now I don't know whether this Hymn of Amon-Ra is at Hibis Temple definitively or even whether it is the first documented example of monism. No, the metalink above is not necessarily the Hymn of Amon-Ra cited by McEvilley. In context, the Hymn to which McEvilley makes reference is cited drawn from Pritchard (1909 – 1997) in ANET (1955: pp.365-367) which in context appears to be drawn from the great temple of Karnak but this is open as the context is ambiguous. There is a large Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak but it is yet to be determined if the Hymn to which McEvilley makes reference is from Karnak or Khageh Oasis. This will require further direct investigation of ANET. The Egyptian texts in ANET were rendered in English from Hieroglyphics by Wilson (1899 - 1976) and not by Pritchard, but McEvilley did not give direct credit.

Hibis Temple in Khargeh Oasis preserves the longest monumental hymns to Amun-Re ever carved in hieroglyphs. These religious texts, inscribed during the reign of Darius I, drew upon a large variety of New Kingdom sources, and later they served as sources for the Graeco-Roman hymns at Esna Temple. As such, the hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis are excellently suited for studying Egyptian theology during the Persian Period, on the eve of the supposed "new theology" created by the Graeco-Roman priesthood.[39]

Why do I feel I need to include Amun-Re? Well Amun may be understood as the archetypal origin of the motif of Nirguna Brahman or Dharmakaya and Ra as the archetypal origin of the motif of Saguna Brahman and Sambhogakaya. This is in the typological and generic sense of first documented auspice for this dichotomy of sacred thought. I am not saying that they directly influenced each other. But for any scholar to argue that pervasion of influence is not a possibility would not only be unsound but untenable.

The Ancient Egyptians envisaged the oceanic abyss of the "Nun" ("The Inert One") as enveloping a sphere in which life is encapsulated, representing the deepest mystery of their cosmogony.[40] In Ancient Egyptian creation accounts the original mound of land issues forth from the primordial waters of the Nun.[41] The Nun is the source of all that appears in a differentiated world, encompassing all aspects of divine and earthly existence. In the Ennead cosmogony Nun is perceived as transcendent at the point of creation alongside Atum the creator god.[42] In Egyptian mythology, Nu ("Watery One") or Nun ("The Inert One") is also the deification of the primordial watery abyss. In the Ogdoad cosmogony, the name nu means "abyss". Nu was shown usually as male but also had aspects that could be represented as female or male. Naunet (also spelt Nunet) is the female aspect, which is the name Nu with a female gender ending. The male aspect, Nun, is written with a male gender ending. As with the primordial concepts of the Ogdoad, Nu's male aspect was depicted as a frog, or a frog-headed man. In Ancient Egyptian iconography, Nun also appears as a bearded man, with blue-green skin, representing water. Naunet is represented as a snake or snake-headed woman. The consort of Nun was sometimes understood to be Neith. Neith had a more rich and divergent attribution and iconography than Nun, but also shared in the personification of the primordial waters originating in the Ogdoad theology, in this capacity Neith like Nun had no gender.

- Beauford excursion to secure ANET texts as they are not available on the Internet.

Akkadian Empire

[edit | edit source]

I didn't even know there was such an empire! It is included as two terms from the Akkadian language were identified by McEvilley as being in the Rig Veda and one of them is regarding "primordial waters". I don't really have any sense of historicity or progression or relationship of the Akkadian Empire with Egypt as yet... but that will come. I don't yet know how the Akkadian terms temporally related to the Egyptian iconography and hieroglyphics and the greater Ancient Near Eastern religion's archetypal mythos of the "primordial waters". Now this is all just disembodied unless I affirm that on Earth life is understood by Science as originating in cellular form in water so this may be a profound intuition of our ancient kin that we have vindicated. Ancestral memory? Cellular memory? Cellular memory unlike genetic memory has received rather fanciful treatment in fiction and sensationalist media but is also a useful concept as evidenced through its citation in a recent reputable work on the science of memory (2007).[43] Or just a bloody good guess? Humans are mostly salt water, so we just adapted to carrying the primordial waters with us upon land. This isn't really so far flung when we remember that in general the Human genome bifurcation that makes a human unique is structured that certain chromosomes from the mother are matrilineal and certain chromosome from the father are patrilineal and both lineages go right back to the first progenitors. The most popular Human ancestry tests are Y chromosome (Y-DNA) testing and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) testing which ascertains direct-line paternal and maternal ancestry, to the Y-chromosomal Adam and Mitochondrial Eve, respectively. Refer The Seven Daughters of Eve (2001). I make this divergence as an aside to affirm a magnificent aspect of human genetics that appears was intuited by the Ancient Near East creation myths and it is poignant to remind the reader and myself that we carry ancient code directly in our genetic constitution.

The following is extracted from the Wikipedia article verbatim and needs to be rewritten and specified: The Akkadian Empire (2334 to 2083 BCE) was an empire centered in the city of Akkad (Sumerian: Agade , Arabic: أكد, Assyrian: ܐܵܟܟܵܐܕ , Hittite KUR A.GA.DÈKI "land of Akkad"; Biblical Accad) and its surrounding region (Akkadian URU Akkad KI)[44] in Ancient Iraq,[45][46] (Mesopotamia). The Akkadian state was the predecessor of the ethnic Akkadian states of Babylonia and Assyria; formed following centuries of Akkadian cultural synergy with Sumerians, it reached the height of its power between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC following the conquests of king Sargon of Akkad, and is sometimes regarded as the first manifestation of an empire in history.[47]

Nondual awareness

[edit | edit source]There are different types of nondual awareness. This is a playful gathering of some of them and they will be thematically discussed and contrasted in due course.

Trikālajña or "knower of the three times [past, present and future]":

- Chalcas the wise, the Grecian Priest and Guide,

- That sacred Seer whose comprehensive View

- The past, the present, and the future knew.

- Pope's The Iliad of Homer

The 'knower of the three times' along with the 'knower of the three worlds' are epithets of many saintly people and divinities, including Shakyamuni and is also poetically attributed by Pope to Chalcas, a sage and seer in his licentious creative construction and poetic adaptation of Homer's Illiad.

An English rendering of the Mahabharata relates the story of Janaka:

"Mention is made of a verse sung (of old) by Janaka who was freed from the pairs of opposites, liberated from desire and enjoyments, and observant of the religion of Moksha. That verse runs thus: 'My treasures are immense, yet I have nothing! If again the whole of Mithila were burnt and reduced to ashes, nothing of mine will be burnt!' As a person on the hill-top looketh down upon men on the plain below, so he that has got up on the top of the mansion of knowledge, seeth people grieving for things that do not call for grief. He, however, that is of foolish understanding, does not see this. He who, casting his eyes on visible things, really seeth them, is said to have eyes and understanding. The faculty called understanding is so called because of the knowledge and comprehension it gives of unknown and incomprehensible things. He who is acquainted with the words of persons that are learned, that are of cleansed souls, and that have attained to a state of Brahma, succeeds in obtaining great honours. When one seeth creatures of infinite diversity to be all one and the same and to be but diversified emanations from the same essence, one is then said to have attained Brahma."[48]

Craig, et.al. (1998: p.476) convey a 'stream of consciousness' or 'mindstream' as a procession of mote events of consciousness (C) with algebraic notation C1, C2 and C3 thus to demonstrate the immediacy of nondual awareness:

That nondual awareness is the only possible self-awareness is defended by a reductio argument. If a further awareness C2, having C1 as content, is required for self-awareness, then since there would be no awareness of C2 without awareness C3, ad infinitum, there could be no self-awareness, that is, unless the self is to be understood as limited to past awareness only. For self-awareness to be an immediate awareness, self-awareness has to be nondual.[49]

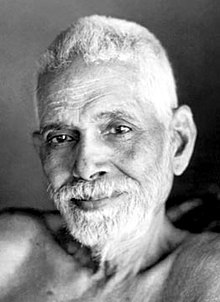

Nisargadatta (1897 – 1981) is reported by Powell (1994, 2006: p.97) stating thus:

...When a stage is reached that one feels deeply that whatever is being done is happening and one has not got anything to do with it, then it becomes such a deep conviction that whatever is happening is not happening really. And that whatever seems to be happening is also an illusion. That may be final. In other words, totally apart from whatever seems to be happening, when one stops thinking that one is living, and gets the feeling that one is being lived, that whatever one is doing one is not doing but one is made to do, then that is a sort of criterion.[50]

Dualism

[edit | edit source]