- News

- City News

- mumbai News

- E-documents admissible as primary evidence in court; safeguards must

Trending

E-documents admissible as primary evidence in court; safeguards must

The last one is from a do-over of the pre-Independence era Indian Evidence Act of 1872 and a recognition of the significance of digital information in today's world.

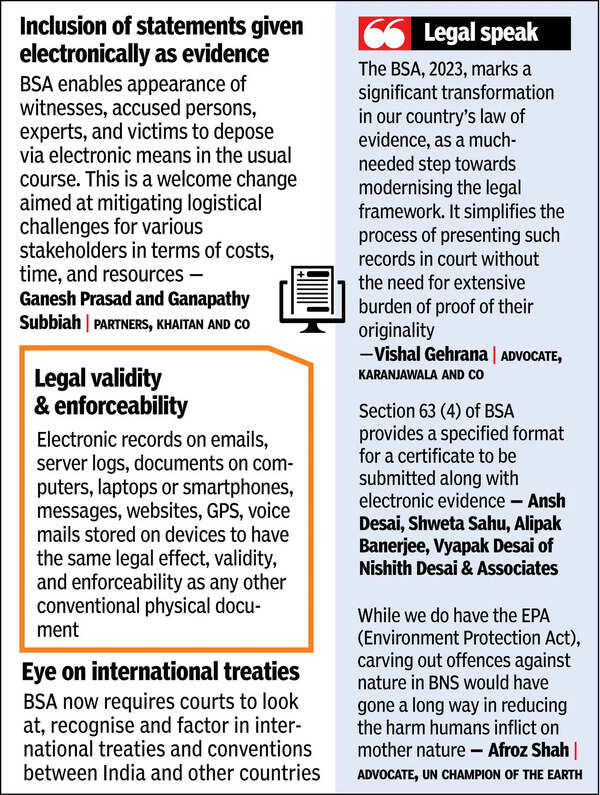

The new law governing what comprises evidence and how it is to be interpreted form the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) of 2023.

It has a provision that factors in technological advances and the widespread use of digital communication saying, subject to various conditions, “an electronic or digital record” can be “admissible” —legal jargon for being accepted as evidence—in a case.

Senior counsel Amit Desai said the question of safeguards must be addressed first over the possible misuse given the unchartered territory of artificial intelligence and emerging software to modify texts, images and digital content on a recipient’s device as well.

Advocate Nusrat Shah recently held two sessions at the Government Law College to an auditorium packed with batches of Mumbai police on the changes and finer aspects of the three new criminal laws, including the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), which replaced the Indian Penal Code of 1860, and Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) in place of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), the procedural rule book.

Shah said BSA’s “singularly significant” addition is Section 57, which makes digital records, including messages, primary evidence, “without much ado,” unless disputed.

“If the digital record is contested, the new law would require a certificate to prove it emanated authentically from a particular computer or digital device,” Shah told TOI.

Thus, under Section 61 of BNS, the court cannot deny the admissibility of an electronic or a digital record subject to certain conditions under Section 63. Any print or copy of an electronic record is a document admissible in any proceeding “without further proof” or production of the original content, provided the device (say, a phone) was being “used regularly” by the person who had “lawful control” of its use.

Senior counsel Aabad Ponda said the term “lawful control” is crucial as it would mean any unlawfully tapped or recorded conversations or videos would not be admissible.

“Digitally recorded conversations will still have to pass the fetters of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1855, that bars illegal phone tap,” said Ponda.

Lawyer Pranav Badheka said given the vast digital landscape (smartphone sales crossed 35 million in the first quarter), the idea is for the law to move with the digital times. “There will be teething problems for sure, and cases will land up before the HC and SC for purposive interpretations of the sections before the ubiquitous text messages can nail someone in a case,” he said.

Under the old Indian Evidence Act, with the use of a certificate under Section 65B, texts could form evidence. Recently, Delhi High Court on July 2 clarified that “WhatsApp conversations cannot be read as evidence without there being a proper certificate as mandated under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872”. The new Acts will apply only to cases that are filed after July 1.

Lawyer Taraq Sayed, who handles cases under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, said it simplifies the procedure for presenting digital records by police and prosecuting agencies. They can “extract” these by many means, not necessarily needing a cyber forensic expert. The information can be downloaded by Bluetooth or with scans too, he said.

There are a lot of voice notes exchanged between alleged drug peddlers that find a mention in chargesheets, he said. “If it’s proved that the phone has been recovered from the suspect, then they would be admissible in court, along with a voice sample to match it with the note,” he added.

While the accused can always dispute its authenticity, the onus is on the prosecution to show how the information was taken from any device, said lawyer Mubin Solkar.

Sayed and Shah also said that phone calls recorded without the other speaker’s knowledge, if found to be “relevant”, could still be admissible, provided the person who recorded it "secretly" deposes before court that it was on his device. However, legal experts are divided on this aspect as it could also be interpreted as a violation of the right to privacy. As Ponda said, “Nothing that violates fundamental rights can be legally sustained.”

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA