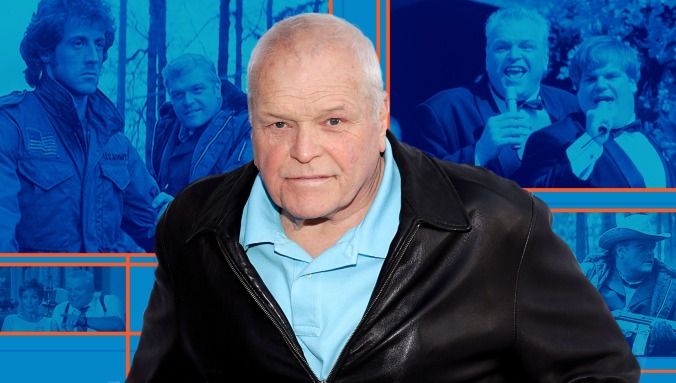

Brian Dennehy on DiCaprio, Rambo, and why Saoirse Ronan is the most talented actor around

Image: Screenshot: Rambo: First BloodScreenshot: Tommy BoyPhoto: John Lamparski/WireImage/Getty ImagesGraphic: Jimmy Hasse

The actor: Brian Dennehy has played everyone from an alien invested in eternal life to a literal rat. In his over 40 years on-screen, he’s become known for his no-bullshit delivery, bulldog physique, and his ability to play both loving fathers and sadistic small-town cops. His latest is a voice-over gig in The Song Of Sway Lake, a Rory Culkin vehicle that’s currently in theaters and on demand. The A.V. Club talked to Dennehy about that role, as well as a number of others—both beloved and forgotten.

Brian Dennehy: I’ll tell ya, I think it’s a sweet picture. It’s beautifully photographed. It has a wonderful, kind of medium-slow rhythm to it, which I like very much. It certainly catches the geography of that place beautifully. And I’m crazy about the woman who played the grandmother. I think I’ve seen her in the past, but I loved her performance, and I loved the way she looks. I just fell in love with her. Her name is Mary Beth Peil.

The kids are great, and it’s an interesting story. I think it’s a good picture. You know, these days with guns and artillery and airplanes and rockets and what’s going on out there, and young people and so forth buying tickets, you never know. But it’s a picture that should have been made, and I’m glad it was made, and I’m glad to be a part of it, even though you just hear my voice, which is probably a good thing for the movie, actually.

I love the locations and the photography, and the lighting was all of a piece, and very, very sweet. It’s interesting, because it captured—I’m old enough to remember, although God knows I didn’t live in that class of people—I was a Brooklyn kid, but I was a Boy Scout. A Cub Scout, and a Boy Scout. So I went to camps in New England and places like that. And the movie really caught that whole quality of that New England, upstate New York camp life, or the environments.

The A.V. Club: According to IMDB, the first thing you were ever in that aired was an episode of Kojak.

BD: That was a long time ago, when they were actually shooting Kojak in New York.

AVC: That same year, you were also on M*A*S*H and Lou Grant, so that must have been an exciting time for you.

BD: I was really just starting out, and I was doing other jobs. I drove a truck, and I worked as a bartender in a lot of different places. But I was trying to be an actor. And then all of the sudden, after 10 years, somebody turned the switch some place. I had been available for a long time, but no one took advantage of that. Then all of the sudden, it got crowded. I started doing a lot of stuff. But better to work than not to work. I barely remember working on Kojak.

AVC: Do you remember being on set, at least?

BD: When you’re shooting a TV series, especially in a place like New York in the middle of the city, it’s amazing how fast they can move, in terms of traffic and so forth. The fact that they get anything at all is astounding. But they do. What happens is it becomes very functional. You get yourself a little trailer that you’re sharing with probably two or three other people. And you go in there, and you put your wardrobe on, and duck into makeup, and they do what they do. You walk back, and you look at the scene that you’re getting ready to shoot, and then bang, you go out and rehearse it. You take five minutes to rehearse it, and then shoot. And then go back to your trailer and wait until they call you for the next one. Or go home because your next shot will be in a different physical environment, which means that you’re shooting on Monday, and all of the sudden you have to come back on Wednesday, and you have four or five hours where you shoot a lot of stuff. But it’s all very fast-moving. And you better know your words, and you better be able to hit a mark. The nature of the beast is—or was in those days—that if you score in a scene with Kojak—what the hell is his name? Good guy.

AVC: Telly Savalas?

BD: Telly, yeah. If you score a scene with him, and people notice, you get another job some other place. Anyway, it’s all fast-moving, and it’s all extremely professional. Whatever emotion that’s called for in the script to play the character, you’re going to provide, because everybody else is just in constant motion and anxious for you to get your goddamn shot and get the hell out of here so they can move.

AVC: You’ve been involved in the entertainment industry for a long time. How do you think it’s changed?

BD: I don’t think the business changes much at all. At least making American movies. Now, I’ve been fortunate enough so that I’ve made movies everywhere. In Europe, in Australia, and South America, and got to see the different attitudes—the personalities, if you will—of the industry in different places. And it’s different everywhere. But in America, it’s like you’re making cars. It’s like you’re working an assembly line in Detroit. It’s fast, and it’s very professional. Extremely professional. You’re expected to do your part, which, if you’re an actor is to supply some emotion at a particular moment, to put something into the lines that would otherwise just sit there as a script.

It doesn’t make any difference whether you feel like you want to do that emotional quality of the scene or not. You have to do it. And you better do it. Because if you can’t do it, if you can’t dredge it up and put it out there in front of the camera, you’re not going to be asked back to the ball.

Back when I was in my mid-30s, I had done a lot of theater, so I knew how to act. And I knew how to get these emotions where they needed to be so that people either could see them in an audience or a camera could pick it up. So that wasn’t a problem. The problem was you just got to do it fast, no matter how many times. Bang. They’d put me on the set. A very quick rehearsal; a guy puts a camera a certain place. “We’re going to do this, this, and this.” Then shoot, and you get the hell out of there because he’s got to do that now 15 different ways all day long with different scenes and different actors. And that’s the way it is. You’ve got 12 hours, 14 hours maybe on some days. And you’re part of a machine that has to move, and hopefully it moves well. Hopefully it moves creatively, but it has to move. Period. It has to move. And you learn how to do that.

Guys like Telly Savalas always impressed the hell out of me because they were so cool. One of the things that Telly had was that great coolness, that sense of being in control all the time. And the guy is working his ass off. He’s constantly moving. But that’s what stardom is, you know? For those guys.

Those were great times. I had a lot of fun, and I didn’t make any money. I was jumping on the subway all the time. I was usually doing a play, so that meant I had to be released from the TV show by 6 or 7 p.m. so I could get to the theater. And it was just a harum-scarum, crazy-ass existence, but of course, I was reasonably young, and it was fun. And it all kind of seemed to be leading some place, so I had a good time. The important thing is you do what you want to do and you do it well, and you have a good time. Okay? One thing about my life is I’ve had a hell of a good time. And I’m glad I did.

AVC: Speaking of plays, you were nominated for an Emmy and won both a SAG Award and a Golden Globe for the TV adaptation of Death Of A Salesman. What do you remember about bringing that play to the screen?

BD: What we did really was film the stage production. In fact, we shot it in the theater. And it was not shot like a movie. It was shot like a documentary of a play. The play was presented to the camera as if the audience was there at the theater. It was never done as a real, outright movie.

I don’t remember much about the movie. I certainly remember doing the play, which I did about 500 times or more. It’s one of the most extraordinary plays… probably the great American play about our country, and the way we are in our personality. I was lucky enough to hit it at the right time in my life and have a great director, Bob Falls. We started in Chicago, came to New York, and then we went to London. We did a whole bunch of different places. Had a wonderful time for two or three years, whatever it was. I became good friends with Arthur Miller, who was the playwright, of course. He and I had some wonderful times together. That was one of the best things about it.

It kind of opened a lot of doors for me. That show, that play, and the fact that it was successful, and my interpretation was accepted as valid. People enjoyed it. I have nothing but good memories about Salesman and gratitude for it.

AVC: You were also in the film adaption of Romeo + Juliet, but that was a considerably bigger production.

BD: [Laughs.] Oh my god, yeah. I’m hardly in that, as I remember. I remember I was in it with… who’s the guy that played Romeo? What’s his name?

AVC: Leonardo DiCaprio.

BD: He was really nice to me. And he was a kid. Seventeen or 18 years old. But he was a huge star. I’ll tell ya, I never saw anybody—especially somebody that age—as relaxed as he was, and has been since. Now, of course, with that talent and the way he looked, he had damn good reason to be relaxed. But still, you’ve got cameras aimed at you from every direction and everybody is there waiting, looking at their watches, wanting to get this scene so they can get onto the next. It’s a hell of a lot of pressure for anybody, but he had no problem with it at all. It was no question that this kid was going to be a huge star, and obviously that’s the way it worked out.

AVC: Can you talk about working with Terrence Malick?

BD: I didn’t spend a lot of time on that project, although I certainly remember fondly working with him. He’s one of those guys. There are a handful of them in the last 100 years or 75 years of making movies. He sees something or reads something or decides they want to do something and because of their genius—and in his case, it is genius and extraordinary talent—they make this concoction of actors and photographers and environment and sets and so forth, and they turn it into a beautiful stew, an amazing dish.

He’s a very, very special guy. He’s had a tremendous career. And I was fortunate enough to get to work with him, and he liked me. We got along well because I essentially would say to him, one way or another, “What do you want in this scene? What do you want from this guy? Forget about the words, forget about the script. What are you looking for from him?” He would come up with some wonderful pointers, and I would try to deliver them. We got along great.

It’s an interesting picture. It was not a huge hit, but it was a piece of art and a beautiful piece of film work. It’s great to be in some of those sometimes. Obviously, you don’t make any money doing them, but what the hell.

AVC: Speaking of singular directors, you’ve also worked with Spike Lee. What was that like?

BD: Spike’s a great guy. And to do what he’s been able to do and to have the kind of success that he’s had is extraordinary. The thing about Spike is he understands what race is all about in this country in a very interesting and very creative way. And so after the two hours you spend in there, you come out knowing more about race. The problems and the difficulties, but also the successes of racial contact. He’s a very interesting analyst about being black in America. He gets that. And he’s made some wonderful stuff.

That’s one of those jobs where you sign onto the project because you want to see what contribution, if any, you can make to the kind of work he does, which is entertaining, but at the same time informative about who we are and what we’re doing in terms of race and how that’s working out. So he’s an important guy.

BD: The funny thing about First Blood is—people forget this now—but Stallone, who had been a sensation of course in Rocky, his career had begun to dim a little bit when we did First Blood. Rocky was so huge, and I don’t know whether he had done the second one by that time. I think he had done it, but it hadn’t come out, and so he was looking for something else. He had done some other pictures, but his career had faded a little bit.

We went up in the winter time to frickin’ British Columbia and shot an exterior picture in the woods freezing our asses off in this beautiful little town up there. Nobody really knew what the hell we had. [Stallone] did it for short money for him, and the guys who made the picture were Canadian. The money guys were from Canada, and an old friend of mine, Ted Kotcheff, directed.

I should have known, because Ted is one of those guys who is a real, old pro. He knew exactly what he was doing. He knew exactly what could happen with that project, and he got it, and we shot it. It took a long time to shoot because of the weather, but when it came out, it exploded. Blew up. It was huge. It was a huge success for Stallone and it was a big success for Ted, because it was obviously a difficult picture to make. People wanted to see the goddamn movie.

I’ll tell you a funny anecdote about that. The original script, which I read and was working on, had Stallone getting killed at the end of the picture. His character, Rambo—I can’t even remember how he died in it. He did not want to be captured. He did not want to have to go back to whatever his post-war life had been, and he was killed. About three weeks into the shoot, they had one of these film markets in L.A. The producers and the director and everybody flew down to L.A. for the weekend and showed a piece of the film. The response, of course, was sensational, both to what Ted directed and what Stallone had done with the character. They came back and said, “By the way, you’re not dying. We’re going to keep you alive,” because they were already thinking in terms of the sequel, which turned into, what? Five sequels?

All of the sudden, they realized what Stallone was. He was so loved by the audience that you can put him in the same parts a little bit later. Those two characters, Rambo and the boxer, he’s done 10? Twelve pictures? Thirteen pictures? Something like that. The point is, they discovered that while they were making that movie, that Stallone was uniquely Stallone. What the audience wanted to see with him was what they had seen before, except somewhat different. They wanted him as Rambo with the problems of getting older, for example. It’s the same thing with Rocky, the boxer. With Rambo, of course, you’ve got him going off to fight wars all over the world, right?

That discovery was made while we were making that picture. The audience’s reaction was so sensational to essentially this short that had been made to show them at this market where people come in from all over the world to buy the picture for future release wherever they lived. The reaction was so extraordinary that it led to not only more successful pictures like that, but then 10 or 15 years of his career, which of course has been extraordinary.

AVC: What do you remember about working with Chris Farley on Tommy Boy?

BD: He was a great guy. Sweet, sweet guy. Comes from a great family. A perfect example of a guy who had everything. Tremendous talent. Wonderful, sweet guy to work with. He had a lot of respect for me because of what I had done, and we hit it off great. David [Spade] was on the picture as well. The two of them were very close.

[Farley] had weaknesses. Obviously the weight was a problem. And he had a profound relationship with John Belushi, who was dead, of course. He had what turned out to be kind of an unhealthy relationship with Belushi, because he lived too close to the flame, as Belushi did. But nice man. A hugely talented man. Very self-destructive, you know, with the booze and the food and so forth—but a decent, decent guy. Good guy. I liked him a lot, and working with him was a sweet pleasure, because we were so creative with each other.

I’m his father in the movie—I think I was his father, anyway—and we meet outside of an office some place, and we’re shooting the scene. I just got crazy, because the point was he was crazy. He was who he was, so what I decided to try to do, improvisationally in a scene, when we met and did that whole meeting thing—“Tommy boy!”—was dance and move around and everything, and he got right into it. And then we had the contest where we both sang the rock ’n’ roll song. I got up to sing, and then he got up to sing. And of course, he was the star, so they asked him, “You want to go first?” I can’t remember where we were. We were at a party, I guess. That’s what it was. Some type of party. And we sang that old… who is the blind singer? The famous blind, black singer?

AVC: Ray Charles?

BD: We did this Ray Charles number, and I just went up and belted it out as hard as I could. So now he feels it necessary that he’s going to top me, right? And he gave it the best shot, but afterward he comes down and says, “I just couldn’t get there to where you were. I feel really bad.” I said, “Hey, hey. I’m your old man. I’m supposed to be bigger than you.” It was that kind of picture where everybody was having fun. And of course, it became a huge hit. Not because of me, because of him.

BD: I’ve done a lot of theater, and I’ve done a lot of Chekhov. I got a message from one of my old theater pals from years ago. I can’t remember who the hell it was now, but they had gone to see The Seagull, and they love what I did with this character. It’s a character that I love, anyway, in the play. And I felt pretty good about it, too. Very, very nice picture. That kid is on her way to being maybe the biggest star ever in the history of the movies. She is amazing.

AVC: Saoirse Ronan?

BD: She is easily, easily the most talented actor I have ever worked with, and that’s saying something. She is the most brilliantly talented actor I have ever worked with. She has a gift that is immeasurable. And every time she works, it knocks people out. There is something about that kid. Hell, what was that movie she was in when she was 12? And she was extraordinary in it?

AVC: Atonement?

BD: Yes. I think she was 20 when we worked together. Maybe 21, 22, but she’s mind-boggling. I mean, you stand there, and you’re in a scene with her, and you better pay attention because your mouth is going to be standing there hanging open. You forget your lines because she’s so extraordinary. She’s really been smart, and the people around her have been very smart about her career. She comes out and she makes a picture, it comes out, there’s this huge critical reception to what she does and awards and all this other stuff, and the picture usually does very well, but then boom—she disappears. She gets out of the way.

She never has to worry about the kind of material she’s going to be given. She never has to worry about how her career is going, because she’s astounding. Astounding. And also terrific to be around, fun. She’s a nice girl. She’s respectful and friendly. She’s not one of these people who is just, “I can’t stand the atmosphere. I’ve got to go to the place and be by myself. I’ll be ready when I’m ready.” She doesn’t do any of that shit. She’s normal and natural and sweet. And then, all of the sudden, she gets in front of a camera and—bing!—she blows the fuckin’ wheels off.

She’s the only actor—male, female, grown-up, adult—the only one, by a mile, who just dazzles you. The simplicity. Her simplicity. The fact that she always plays against the grain of the scene. I mean, she can be very big. She can be very dramatic and very funny, but whatever she does—whatever she fuckin’ does—surprises you.

She’s just an incredible talent. She’s the greatest acting talent I’ve ever worked with, and I have worked with everybody. I’ve worked with great actors. And she’s a great actor, but there’s something else there. There’s something else going on with her. I don’t know what it is, but she’s got these eyes that look like they’re 10,000 years old and have seen everything. That’s does not mean that she looks old; I don’t mean that. I mean she understands things, and her talent is such that she can take the scene, take the words, take the environment, the other actors, take the furniture, and make it all into one seamless reality that is profound. There’s a deep, profound reality coming out of her eyes. As far as I’m concerned, there’s her, and then there’s other people. She’s in a class by herself, literally.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.