Analytic Geometry. by H. B.: Shorter Notices

Analytic Geometry. by H. B.: Shorter Notices

Uploaded by

Wignadze Temo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views4 pagesThis document summarizes a two-volume work titled "A Budget of Paradoxes" by Augustus De Morgan. It provides details on the original publication of the work in the Athenaeum journal from 1863 to 1866. It was later republished after De Morgan's death in 1872 by his widow, with some additions. The current two-volume edition was edited by David Eugene Smith and republished by The Open Court Publishing Company in 1915. The review provides background on the author and original circumstances for the popular writing, and evaluates some aspects of the mechanical features and scope of the current edition.

Original Description:

Original Title

1183423676

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes a two-volume work titled "A Budget of Paradoxes" by Augustus De Morgan. It provides details on the original publication of the work in the Athenaeum journal from 1863 to 1866. It was later republished after De Morgan's death in 1872 by his widow, with some additions. The current two-volume edition was edited by David Eugene Smith and republished by The Open Court Publishing Company in 1915. The review provides background on the author and original circumstances for the popular writing, and evaluates some aspects of the mechanical features and scope of the current edition.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views4 pagesAnalytic Geometry. by H. B.: Shorter Notices

Analytic Geometry. by H. B.: Shorter Notices

Uploaded by

Wignadze TemoThis document summarizes a two-volume work titled "A Budget of Paradoxes" by Augustus De Morgan. It provides details on the original publication of the work in the Athenaeum journal from 1863 to 1866. It was later republished after De Morgan's death in 1872 by his widow, with some additions. The current two-volume edition was edited by David Eugene Smith and republished by The Open Court Publishing Company in 1915. The review provides background on the author and original circumstances for the popular writing, and evaluates some aspects of the mechanical features and scope of the current edition.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

1916.] SHORTER NOTICES.

465

Thomas Heath to say that the care shown by each, in the

editing of the classics to which their names attach, is on a par

with that shown by the other. Certainly we have not had

any such work done before in this country in the editing of

any Greek mathematical text, and the thanks and appreciation

of Professor Archibald's colleagues will go out to him in

abundant measure for his excellent contribution to the

literature of the subject.

Not the least of the commendable features of the edition

under review is the bibliography of works relating to the

division of figures. How complete this is it is difficult to

say, since one would have to go through a large amount of

material, as has evidently been done in this case, to determine

just where to find points of contact with the " De Divisionibus."

At any rate the list is a very helpful one and adds materially

to the value of the work.

The publishers have allowed the printing of a copious index

of names, and have issued the work in the dignified form which

always characterizes the output of the Cambridge University

Press.

DAVID EUGENE SMITH.

Analytic Geometry. By H. B. PHILLIPS. New York, John

Wiley and Sons, 1915. vii+197 pp.

IN the preface of this book the author expresses the belief

that for engineering students " a short course in analytic ge-

ometry is essential"; and "he has, therefore, written this text

to supply a course that will equip the student for work in

calculus and engineering without burdening him with a mass

of detail useful only to the student of mathematics for its own

sake." At first glance the comparatively small number of

pages would seem to promise such a short course. But a

closer examination led the present writer to the opinion that

the apparent brevity was achieved by condensation, and that

it would require as much time to cover these 197 pages as to

cover say 300 pages of many other texts. Except for the

omission of some of the special properties of the conies, it

did not seem quite obvious that the student's burden of a

mass of detail was conspicuously lightened.

On the other hand, the author at times assumes a clearness

of mathematical vision and a facility in technique on the

part of the student which would be eminently desirable, but

466 SHORTER NOTICES. [June,

which we fail to find in a majority of our college students.

For instance, after learning (page 94) that "a curve is sym-

metrical with respect to the origin if all the terms in its equa-

tion are of even degree or if all are of odd degree," we find the

following example (I quote the text exactly) :

((

y = xz — 3#2 + 3x + 1. This equation can be written

y - 2 = (x - l) 3 .

The expressions y — 2 and x — 1 are the coordinates of a

point P(x, y) relative to the lines y = 2, x = 1 used as axes.

Since the equation contains only odd powers of y — 2 and

x — 1, the curve is symmetrical with respect to the point

(1, 2)." This occurs 50 pages earlier than the treatment of

transformations to parallel axes. At such points the ordinary

student will certainly need the help of the teacher. However,

many teachers will find this no objection to the book, but will

prefer to use a text which leaves to the teacher some further

function than the assigning of lessons and the conducting of

recitations. Teachers with ideas of their own are sometimes

hampered by a text too liberal in its explanations.

The first chapter, on algebraic principles, furnishes a good

review of those parts of algebra which are most necessary

for what follows. One is pleased to find a discussion of in-

equalities and of homogeneous linear equations. In the

second chapter, introducing rectangular coordinates, there are

six excellent pages on vectors. The straight line and circle

are treated in chapter three, which is short but would seem to

furnish the student with the necessary working equipment.

A very good feature is the clear exposition of the geometrical

significance of the sign of the expression Ax + By + C; but it

is to be regretted that the idea was not used to the best ad-

vantage later; as, for instance, in connection with the distance

formula (Axi + Byi + C)/ ± V^42 + B2, and the definition of

the hyperbola.

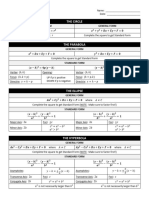

After a somewhat unusual treatment of the conies in chapter

four, one finds a very interesting chapter on graphs and em-

pirical equations. In addition to the usual curve drawing,

the problem of fitting a curve to a number of given pairs of

values of the variables is discussed, with a number of exercises

drawn from mechanics, electricity, chemistry, etc. Chapters

six, seven, and eight are devoted respectively to polar coordi-

nates, parametric representation, and transformations. The

1916.] SHORTER NOTICES. 467

chapter on parametric representation, with the development

of the equations of the cycloidal and other curves, is one of

the excellent features of the book. The last three chapters

present very briefly the first elements of the analytic geometry

of space, treating the plane, straight line, sphere, cylindrical

surfaces, surfaces of revolution, and the different quadric

surfaces in their simplest positions. The helix is discussed in

a very short paragraph on parametric equations of space

curves.

The author's treatment of conies should have special men-

tion. The ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola are defined as

follows:

"If a circle is deformed in such a way that the distances of

its points from a fixed diameter are all changed in the same

ratio, the resulting curve is called an ellipse.

"Let LK, RS be perpendicular lines and MP, NP perpen-

diculars from any point P to them. If a is constant and

NP considered positive when P is on one side of RS, negative

when on the other, the locus of points P such that

MP2 = a • NP

is called a parabola.

"Let KL tod RS be two straight lines intersecting in C,

PM and PN the perpendiculars from any point P to these

lines. Let MP be considered positive when P is on one side

of KL, negative when on the other side. Similarly, let NP

be positive when P is on one side of RS, negative when on the

other side. A hyperbola is the locus of points P such that the

product

MP • NP = constant."

The general definition of a conic, and the classification with

respect to the eccentricity are given later in the chapter on

polar coordinates. There is no question here of correctness or

incorrectness, but merely one of taste and expediency. Many

teachers would prefer that the conies should be first intro-

duced by a general definition ; and many others, willing to use

independent definitions of the three types, would prefer other

definitions than those which the author has seen fit to use.

Immediately following the definition of the parabola we read:

"A parabola is thus a locus of points the squares of whose

distances from one of two perpendicular lines are proportional

to their distances from the other. The complete locus of

468 SHORTER NOTICES. [June,

such points is two parabolas, one on each side of RS." A

similar statement follows the definition of the hyperbola. Is

it not unfortunate to speak of a locus which is not a complete

locus?

The definition of equivalence of sets of equations (page 3)

is somewhat vague; and it hardly seems wise to say that the

equation (x + y){x — 2y) = 0 is equivalent to the two

equations x + y = 0 and x — 2y = 0, even though the sense

in which this is meant is immediately explained.

The statement (page 15) that "a set of homogeneous equa-

tions can often be solved for the ratios of the variables when

there are not enough equations to determine the exact values"

might seem to imply that the "exact" values could be deter-

mined if there were enough equations.

In chapter five there is a paragraph on "infinite values"

which reminds one of the school algebras of the last generation.

It seemed to the present writer to be a really serious defect in

what is in many respects an excellent book.

The mechanical features of the book are attractive, the

figures (with a few exceptions) are accurate, and the typo-

graphical work is free from errors.

WALTER B. CARVER.

A Budget of Paradoxes. By AUGUSTUS D E MORGAN. Re-

printed, with the author's additions, from the Athenœum.

Second edition, edited by DAVID EUGENE SMITH. Two

volumes, I, viii+402 pp.; II, 387 pp. Chicago, The Open

Court Publishing Co., 1915. Price, $3*50 per volume.

THE first edition of this interesting work by Augustus De

Morgan (1806-1871) appeared in 1872, after the author's

death, under the editorship of his widow, Sophia De Morgan.

Some ten years later Mrs. De Morgan wrote a "Memoir of

Augustus De Morgan," which is worthy of mention in con-

nection with the "Budget of Paradoxes." De Morgan's

articles which constitute the present work appeared from time

to time, in the years from 1863 (Oct. 10) to 1866 (Dec. 1), in

the London Athenœum. From other facts which we have

concerning the life of De Morgan it appears that some of the

popular writing which he did, for encyclopedias and for jour-

nals, was stimulated by financial pressure; at this distance we

can properly rejoice at the conditions which fostered the growth

of the present work.

You might also like

- Ricci-Calculus - An Introduction To Tensor Analysis and Its Geometrical ApplicationsDocument535 pagesRicci-Calculus - An Introduction To Tensor Analysis and Its Geometrical ApplicationsAliBaranIşık100% (4)

- Elliptic Tales: Curves, Counting, and Number TheoryFrom EverandElliptic Tales: Curves, Counting, and Number TheoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Mathematics IN AGRICULTURE PDFDocument144 pagesMathematics IN AGRICULTURE PDFAndres Brutas100% (6)

- 1st Quarter PrecalDocument3 pages1st Quarter PrecalZoe Sarah Bejuco100% (2)

- BookReview-Of Netz DeductionDocument6 pagesBookReview-Of Netz DeductiongfvilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To Differential Geometry. by T. J. Willmore. New YorkDocument3 pagesAn Introduction To Differential Geometry. by T. J. Willmore. New YorkCharmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Functions of A Complex Variable. byDocument8 pagesFunctions of A Complex Variable. bycrovaxIIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Ciencia de MoultonDocument2 pagesCiencia de MoultonGia OrionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardinal and Ordinal Numbers. by W. Sierpióski. Monografie MateDocument3 pagesCardinal and Ordinal Numbers. by W. Sierpióski. Monografie MateSong LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- K Is & More or Less Accurate Measure Of: Book ReviewsDocument5 pagesK Is & More or Less Accurate Measure Of: Book ReviewssafarioreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Treatise on the Differential Geometry of Curves and SurfacesFrom EverandA Treatise on the Differential Geometry of Curves and SurfacesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classical Di Erential Geometry of CurvesDocument118 pagesClassical Di Erential Geometry of CurvesHamilton C RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Geometry According To Euclid: Robin HartshorneDocument6 pagesTeaching Geometry According To Euclid: Robin HartshornepmhzsiluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math. 467: Modern Geometry: First DayDocument7 pagesMath. 467: Modern Geometry: First DayJondel IhalasNoch keine Bewertungen

- PappusDocument13 pagesPappuswrath09Noch keine Bewertungen

- Landsman, N. P. - Mathematical Topics Between Classical and Quantum Mechanics-Springer New York (1998)Document547 pagesLandsman, N. P. - Mathematical Topics Between Classical and Quantum Mechanics-Springer New York (1998)CroBut CroButNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bessel Functions For Engineers. by N. W. Mclachlan. Oxford, Clarendon PressDocument2 pagesBessel Functions For Engineers. by N. W. Mclachlan. Oxford, Clarendon PressDIEGO MAX SILVA LOPESNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArbelosDocument14 pagesArbelosmzambrano2Noch keine Bewertungen

- B Kolman Introductory Linear Algebra With Applications Macmillan 1976 Xvi426 PPDocument2 pagesB Kolman Introductory Linear Algebra With Applications Macmillan 1976 Xvi426 PPSoung WathannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Hilbert Space and the Theory of Spectral Multiplicity: Second EditionFrom EverandIntroduction to Hilbert Space and the Theory of Spectral Multiplicity: Second EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Algebra (Ferrar) PDFDocument238 pagesAlgebra (Ferrar) PDFJonathan Burros100% (1)

- The Great Art or The Rules of AlgebraDocument6 pagesThe Great Art or The Rules of AlgebraAlae sayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Some Recent Books (Continued) : W. G. Bickley A N D R. S. H. G. ThompsonDocument2 pagesSome Recent Books (Continued) : W. G. Bickley A N D R. S. H. G. ThompsonAshiqueHussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bishop Constructive AnalysisDocument23 pagesBishop Constructive Analysismalik jozsef zoltan100% (1)

- T I WillmoreDocument2 pagesT I WillmoreankitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Higher Geometry: An Introduction to Advanced Methods in Analytic GeometryFrom EverandHigher Geometry: An Introduction to Advanced Methods in Analytic GeometryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lambert GBDocument24 pagesLambert GBAthanase PapadopoulosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lie Algebra: A Beginner's ApproachDocument279 pagesLie Algebra: A Beginner's ApproachBen100% (2)

- 31151006451797Document408 pages31151006451797usbv135wNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simmons PraiseDocument5 pagesSimmons Praisecart_thickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helgason - Sophus Lie, The MathematicianDocument19 pagesHelgason - Sophus Lie, The MathematicianZow Niak100% (1)

- EUCLID, The ElementsDocument17 pagesEUCLID, The ElementsMd Mahamudul Hasan HimelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selected Topics in Three-Dimensional Synthetic Projective Geometry-Introduction, References, and IndexDocument18 pagesSelected Topics in Three-Dimensional Synthetic Projective Geometry-Introduction, References, and IndexjohndimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles: Why Ellipses Are Not Elliptic CurvesDocument14 pagesArticles: Why Ellipses Are Not Elliptic CurvescoolsaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mackay Early History of The Symmedian PointDocument12 pagesMackay Early History of The Symmedian PointgrigoriytamasjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hideyuki Matsumura Commutative Ring Theory Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 8 Cambridge University Press 1986 PP 320 Pound30Document2 pagesHideyuki Matsumura Commutative Ring Theory Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 8 Cambridge University Press 1986 PP 320 Pound30geoguoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TheUniversalEncyclopediaOfMathematics TextDocument718 pagesTheUniversalEncyclopediaOfMathematics TextSileman100% (1)

- Hestnes 1986 - Clifford Algebra and The Interpretation of Quantum MechanicsDocument18 pagesHestnes 1986 - Clifford Algebra and The Interpretation of Quantum MechanicsRanjan BasuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geometry Affine (1) AcuanDocument22 pagesGeometry Affine (1) AcuanFahruh JuhaevahNoch keine Bewertungen

- tm111 PDFDocument22 pagestm111 PDFAmit ParmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of NonEuclidean Geometry and TrigonometryDocument198 pagesElements of NonEuclidean Geometry and TrigonometryVishnu Sarma100% (1)

- Projective GeometryDocument366 pagesProjective Geometryhummingbird_hexapla100% (5)

- EulerDocument15 pagesEulershivu_bn5341Noch keine Bewertungen

- Oscar Zariski, Peirre Samuel - Commutative Algebra, Vol I, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 28, Springer (1965) PDFDocument341 pagesOscar Zariski, Peirre Samuel - Commutative Algebra, Vol I, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 28, Springer (1965) PDFJavi Orts100% (2)

- Elliptic Integral PDFDocument114 pagesElliptic Integral PDFlagrange7100% (2)

- An ElementaryTreatise On The Geometry of Conics Mukhopadhyay 1893Document254 pagesAn ElementaryTreatise On The Geometry of Conics Mukhopadhyay 1893Just BarryNoch keine Bewertungen

- პარამეტრიანი ამოცანტები (ვისოცკი)Document316 pagesპარამეტრიანი ამოცანტები (ვისოცკი)Wignadze TemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 112 საინტერესპ გეომეტრიული ამოცანა ამოხსნებითDocument36 pages112 საინტერესპ გეომეტრიული ამოცანა ამოხსნებითWignadze TemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1761 3 FM Skerco Azarashvili VajaDocument26 pages1761 3 FM Skerco Azarashvili VajaWignadze TemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1329 3 FM Sonata Azarashvili VajaDocument46 pages1329 3 FM Sonata Azarashvili VajaWignadze TemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toefl SpeakingDocument7 pagesToefl SpeakingWignadze TemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9-3 Parabolas PDFDocument14 pages9-3 Parabolas PDFMc BolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forgettable But Important Points - ConicsDocument13 pagesForgettable But Important Points - Conicssudhanshu.maluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit FP1 Further Pure Mathematics 1Document5 pagesUnit FP1 Further Pure Mathematics 1Nushran NufailNoch keine Bewertungen

- MY Iit - Jee Preparation: Chapter-2Document32 pagesMY Iit - Jee Preparation: Chapter-2kenneth kilianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan DCG Ellipses Parabolas EccentricityDocument5 pagesLesson Plan DCG Ellipses Parabolas Eccentricityapi-606281050Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ellipse Theory eDocument18 pagesEllipse Theory ethinkiit67% (3)

- The ParabolaDocument10 pagesThe ParabolaShoaib AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excursions in GeometryDocument185 pagesExcursions in Geometryrgshlok80% (10)

- Desargues Trong X NHDocument7 pagesDesargues Trong X NHAristotle PytagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class 11 MathematicsDocument9 pagesClass 11 Mathematicsanand maheshwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conic Sections Unit Test 2009Document6 pagesConic Sections Unit Test 2009Christopher RousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Calc - Unit 4 - ReviewDocument6 pagesPre-Calc - Unit 4 - ReviewArjay PidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Drawing Unit - IDocument189 pagesEngineering Drawing Unit - IK S Chalapathi100% (1)

- Engineering Graphics Manual FinalDocument99 pagesEngineering Graphics Manual Finalgpt krtlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rsm-Phase Plan-Pcm-2019 - 21Document2 pagesRsm-Phase Plan-Pcm-2019 - 21Priyadarshi KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q ParabolasDocument2 pagesQ Parabolasapi-339611548Noch keine Bewertungen

- Apollonius and Conic Sections: A. Some HistoryDocument17 pagesApollonius and Conic Sections: A. Some HistorydmoratalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wbjee-2011 Previous Year Question-Paper WithSolution PDFDocument56 pagesWbjee-2011 Previous Year Question-Paper WithSolution PDFSourav SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutorial Tutorial: SECTION - A (Aimstutorial - In) SECTION - A (Aimstutorial - In)Document4 pagesTutorial Tutorial: SECTION - A (Aimstutorial - In) SECTION - A (Aimstutorial - In)M.SHOURYA VARDHANNoch keine Bewertungen

- cs602 - Midterm Solved McqsDocument24 pagescs602 - Midterm Solved McqsEisha Ghazal100% (1)

- Ge 6152 Engineering Graphics Anna University Question Bank - I Plane Curves & Freehand SketchingDocument14 pagesGe 6152 Engineering Graphics Anna University Question Bank - I Plane Curves & Freehand SketchingArul JothiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13-Chapter 13 - Kinematics of Particle-Force & AccelerationDocument65 pages13-Chapter 13 - Kinematics of Particle-Force & AccelerationMuhammad Anaz'sNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solution For Es Objective MechanicalDocument45 pagesSolution For Es Objective MechanicalROHIT PANCHALNoch keine Bewertungen

- +1 CBSE - MATHS CDF MATERIAL (01-36) .PMDDocument36 pages+1 CBSE - MATHS CDF MATERIAL (01-36) .PMDcernpaul100% (1)

- Precal Exam G11 Q1 AnswerDocument5 pagesPrecal Exam G11 Q1 AnswerMochi. PJMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Drawing. Assignment PDFDocument28 pagesEngineering Drawing. Assignment PDFAsif KhanzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 Introduction To Conic Sections and Circles Week 3Document10 pagesChapter 2 Introduction To Conic Sections and Circles Week 3Angelo ResuelloNoch keine Bewertungen