Rationale for Switching or Simplifying Antiretroviral Therapy

There are many reasons why a patient may potentially benefit from a change in antiretroviral therapy, even when they have consistently suppressed HIV RNA levels. Common reasons to consider switching antiretroviral therapy in the setting of virologic suppression include managing or preventing short-term or long-term adverse effects, high pill burden, difficulties with food requirements, or problematic drug interactions.[1,2,3] Additional considerations may include pregnancy, cost, changes to insurance coverage, or a desire to match a partner’s regimen. These reasons for switching an antiretroviral regimen are distinct from switching a regimen in the setting of virologic failure with documented antiretroviral resistance, which necessitates transitioning to a salvage regimen as guided by genotypic drug resistance testing.

Updating Antiretroviral Therapy to a Modern Regimen

One frequent reason that antiretroviral therapy switches are considered in clinical practice is to “update” a regimen that is no longer recommended as part of first-line or alternative antiretroviral therapy. In this situation, a regimen modification may benefit the person with HIV by reducing pill burden, eliminating food restrictions, and decreasing the risk for long-term adverse effects. There are some older antiretroviral agents that should no longer be used in modern practice and should typically be updated to newer options in order to improve tolerability and reduce potential side effects. For example, certain protease inhibitors (PIs), including lopinavir-ritonavir, saquinavir, nelfinavir, indinavir, fosamprenavir, and tipranavir, should be replaced by boosted darunavir, boosted atazanavir, or a medication from another drug class. In addition, old nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)—zidovudine, didanosine, and stavudine—typically should be replaced by a newer NRTI or another medication from another medication class. In addition, most experts would also recommend updating older non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NNRTIs), such as nevirapine and efavirenz, to a newer NNRTI or a medication from another drug class. If a patient is taking an antiretroviral regimen that includes one or more of the outdated medications noted above, clinicians should consider obtaining expert consultation to help with optimizing and updating the new antiretroviral regimen.

Switching Regimen to Reduce Pill Burden

Persons with HIV may request a change of antiretroviral therapy to reduce pill burden for the sake of convenience. If this change can be safely made with a high likelihood of maintaining virologic suppression, there may be long-term benefits associated with simplifying the antiretroviral regimen. Multiple studies have demonstrated that taking fewer pills translates to better adherence and higher rates of long-term virologic control.[4,5,6,7,8] Furthermore, as the population of individuals living with HIV ages, they will increasingly need to take more medications for non-HIV-related conditions, leading to added polypharmacy and treatment complexity, thus increasing the benefit of simpler antiretroviral therapy combinations.[3,9,10] Simplifying antiretroviral therapy may also have a significant economic impact, including lower copayments for the patient, particularly if the switch involves a reduction in the number of medications in the regimen.[11,12] By contrast, as more antiretroviral medications become available as generic preparations, a switch from an older medication (available as generic) to a new medication may increase the overall cost of the regimen; access to new medications and insurance coverage are important considerations before any antiretroviral therapy changes.

Factors to Consider Before Switching or Simplifying Therapy

The principal goal of any antiretroviral therapy switch is to improve a patient’s quality of life while maintaining virologic suppression.[1,3] Taking this overarching goal into consideration, a clinician contemplating a modification of antiretroviral therapy for a patient with consistently suppressed HIV RNA levels should consider multiple factors related to past history: prior antiretroviral therapy regimens, past virologic failures, documented drug resistance, medication adherence, and past or current intolerance to antiretroviral medications. Any potential switch of antiretroviral therapy should assimilate a composite of all past drug resistance test results. Furthermore, it is essential to review a patient’s active medication list for potential drug interactions (including herbal and over-the-counter medications) and consider food requirements, potential side effects, and cost or availability of the new regimen. A past history of virologic failure is particularly important when considering a switch from a regimen that has an anchor drug with a relatively higher genetic barrier to resistance to one with a relatively lower barrier to resistance, even if the individual has suppressed HIV RNA levels at the time the switch is considered. If considering a switch from an agent or regimen of relatively higher barrier to resistance to an agent or regimen of relatively lower barrier to resistance, it is imperative to ensure that there is no underlying resistance (to any component of the new regimen) that may have been overcome by the potency of the prior regimen, but that will compromise the efficacy of the new combination.

Validity of Antiretroviral Switch Studies

A number of clinical trials have examined the effects of switching antiretroviral therapy for patients with suppressed HIV RNA levels. Interpreting the results of antiretroviral therapy switch studies requires some caution, as these trials are often sponsored by industry and are frequently (though not always) designed as open-label trials, which may lead to bias against reporting adverse events. In addition, patients may enroll in these types of studies with a preference for randomization to the switch-therapy arm, which may lead to differential dropout from the control arm. Taken together, these factors may create a degree of inherent bias in switch trials. Despite these limitations, switch studies have generated abundant data, as well as a number of key lessons, that provide imperative clinical reminders when considering an antiretroviral therapy regimen change.

Monitoring After Antiretroviral Switch or Simplification

After making a switch or simplification to an antiretroviral regimen, it is important to plan for close follow-up during the first 3 months after the regimen change. This follow-up should include confirming the patient is taking the new combination appropriately, evaluating for medication tolerance, and obtaining an HIV RNA level within 4 to 8 weeks after the regimen change.[1]

Bictegravir-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Biktarvy

Bictegravir-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Biktarvy Darunavir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Symtuza

Darunavir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Symtuza Dolutegravir-Abacavir-Lamivudine Triumeq

Dolutegravir-Abacavir-Lamivudine Triumeq Dolutegravir-Lamivudine Dovato

Dolutegravir-Lamivudine Dovato Dolutegravir-Rilpivirine Juluca

Dolutegravir-Rilpivirine Juluca Doravirine-Tenofovir DF-Lamivudine Delstrigo

Doravirine-Tenofovir DF-Lamivudine Delstrigo Efavirenz-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Atripla

Efavirenz-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Atripla Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Genvoya

Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Genvoya Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Stribild

Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Stribild Rilpivirine-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Odefsey

Rilpivirine-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Odefsey Rilpivirine-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Complera

Rilpivirine-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Complera Enfuvirtide Fuzeon

Enfuvirtide Fuzeon Fostemsavir Rukobia

Fostemsavir Rukobia Ibalizumab Trogarzo

Ibalizumab Trogarzo Maraviroc Selzentry

Maraviroc Selzentry Dolutegravir Tivicay

Dolutegravir Tivicay Raltegravir Isentress

Raltegravir Isentress Abacavir Ziagen

Abacavir Ziagen Abacavir-Lamivudine Epzicom

Abacavir-Lamivudine Epzicom Abacavir-Lamivudine-Zidovudine Trizivir

Abacavir-Lamivudine-Zidovudine Trizivir Didanosine Videx

Didanosine Videx Emtricitabine Emtriva

Emtricitabine Emtriva Lamivudine Epivir

Lamivudine Epivir Stavudine Zerit

Stavudine Zerit Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Descovy

Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Descovy Tenofovir DF Viread

Tenofovir DF Viread Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Truvada and Multiple Generics

Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Truvada and Multiple Generics Zidovudine Retrovir

Zidovudine Retrovir Zidovudine-Lamivudine Combivir

Zidovudine-Lamivudine Combivir Doravirine Pifeltro

Doravirine Pifeltro Efavirenz Sustiva

Efavirenz Sustiva Etravirine Intelence

Etravirine Intelence Nevirapine Viramune

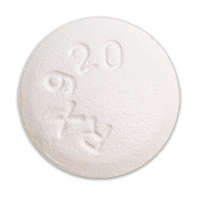

Nevirapine Viramune Rilpivirine Edurant

Rilpivirine Edurant Atazanavir Reyataz

Atazanavir Reyataz Atazanavir-Cobicistat Evotaz

Atazanavir-Cobicistat Evotaz Darunavir Prezista

Darunavir Prezista Darunavir-Cobicistat Prezcobix

Darunavir-Cobicistat Prezcobix Fosamprenavir Lexiva

Fosamprenavir Lexiva Indinavir Crixivan

Indinavir Crixivan Lopinavir-Ritonavir Kaletra

Lopinavir-Ritonavir Kaletra Nelfinavir Viracept

Nelfinavir Viracept Saquinavir Invirase

Saquinavir Invirase Tipranavir Aptivus

Tipranavir Aptivus Cobicistat Tybost

Cobicistat Tybost Ritonavir Norvir

Ritonavir Norvir