Background and Overview

Despite the widespread availability and use of potent antiretroviral therapy, individuals with HIV continue to suffer significant morbidity and mortality from opportunistic infections, defined as infections that are more frequent or severe due to immunosuppression. The introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy in the mid-1990s led to a dramatic decline in the rate of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections in the United States (Figure 1), and these declines involved all major AIDS-defining opportunistic infections (Figure 2).[1,2] During 2000 through 2010 (in the United States and Canada), AIDS-defining opportunistic infections occurred at a low rate and there were further declines during this decade (Figure 3).[3] In the current era, the rate of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections has remained low. Nevertheless, these opportunistic infections can still occur in individuals with HIV, particularly in the setting of undiagnosed HIV, late diagnosis of HIV, or in persons with known HIV who are not engaged in care. Clinicians who provide care to persons with HIV should have basic competency in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of common AIDS-defining opportunistic infections. This Topic Review provides an overview of the prophylaxis of the most common and important opportunistic infections that occur in persons with HIV. The content is based on recommendations in the Adult and Adolescent OI Guidelines.[4]

Bictegravir-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Biktarvy

Bictegravir-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Biktarvy Darunavir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Symtuza

Darunavir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Symtuza Dolutegravir-Abacavir-Lamivudine Triumeq

Dolutegravir-Abacavir-Lamivudine Triumeq Dolutegravir-Lamivudine Dovato

Dolutegravir-Lamivudine Dovato Dolutegravir-Rilpivirine Juluca

Dolutegravir-Rilpivirine Juluca Doravirine-Tenofovir DF-Lamivudine Delstrigo

Doravirine-Tenofovir DF-Lamivudine Delstrigo Efavirenz-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Atripla

Efavirenz-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Atripla Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Genvoya

Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Genvoya Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Stribild

Elvitegravir-Cobicistat-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Stribild Rilpivirine-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Odefsey

Rilpivirine-Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Odefsey Rilpivirine-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Complera

Rilpivirine-Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Complera Enfuvirtide Fuzeon

Enfuvirtide Fuzeon Fostemsavir Rukobia

Fostemsavir Rukobia Ibalizumab Trogarzo

Ibalizumab Trogarzo Maraviroc Selzentry

Maraviroc Selzentry Dolutegravir Tivicay

Dolutegravir Tivicay Raltegravir Isentress

Raltegravir Isentress Abacavir Ziagen

Abacavir Ziagen Abacavir-Lamivudine Epzicom

Abacavir-Lamivudine Epzicom Abacavir-Lamivudine-Zidovudine Trizivir

Abacavir-Lamivudine-Zidovudine Trizivir Didanosine Videx

Didanosine Videx Emtricitabine Emtriva

Emtricitabine Emtriva Lamivudine Epivir

Lamivudine Epivir Stavudine Zerit

Stavudine Zerit Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Descovy

Tenofovir alafenamide-Emtricitabine Descovy Tenofovir DF Viread

Tenofovir DF Viread Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Truvada and Multiple Generics

Tenofovir DF-Emtricitabine Truvada and Multiple Generics Zidovudine Retrovir

Zidovudine Retrovir Zidovudine-Lamivudine Combivir

Zidovudine-Lamivudine Combivir Doravirine Pifeltro

Doravirine Pifeltro Efavirenz Sustiva

Efavirenz Sustiva Etravirine Intelence

Etravirine Intelence Nevirapine Viramune

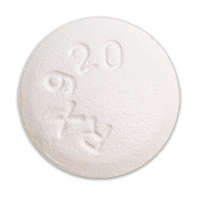

Nevirapine Viramune Rilpivirine Edurant

Rilpivirine Edurant Atazanavir Reyataz

Atazanavir Reyataz Atazanavir-Cobicistat Evotaz

Atazanavir-Cobicistat Evotaz Darunavir Prezista

Darunavir Prezista Darunavir-Cobicistat Prezcobix

Darunavir-Cobicistat Prezcobix Fosamprenavir Lexiva

Fosamprenavir Lexiva Indinavir Crixivan

Indinavir Crixivan Lopinavir-Ritonavir Kaletra

Lopinavir-Ritonavir Kaletra Nelfinavir Viracept

Nelfinavir Viracept Saquinavir Invirase

Saquinavir Invirase Tipranavir Aptivus

Tipranavir Aptivus Cobicistat Tybost

Cobicistat Tybost Ritonavir Norvir

Ritonavir Norvir